Understanding ASP.NET 5 Configuration

Note: just prior to press time, Microsoft announced name changes to ASP.NET 5 and related stacks. ASP.NET 5 is now ASP.NET Core 1.0. Entity Framework (EF) 7 is now Entity Framework (EF) Core 1.0. The ASP.NET 5 and EF7 packages and namespaces will change, but otherwise the new nomenclature has no impact on the lessons of this article.

Those of you working with ASP.NET 5 have no doubt noticed the new configuration support included in that platform and available in the Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration collection of NuGet packages. The new configuration allows a list of name-value pairs, which can be grouped into a multi-level hierarchy. For example, you can have a setting stored in SampleApp:Users:InigoMontoya:MaximizeMainWindow and another stored in SampleApp:AllUsers:Default:MaximizeMainWindow. Any stored value maps to a string, and there’s built-in binding support that allows you to deserialize settings into a custom POCO object. Those of you already familiar with the new configuration API probably first encountered it within ASP.NET 5. However, the API is in no way restricted to ASP.NET. In fact, all the listings in this article were created in a Visual Studio 2015 Unit Testing project with the Microsoft .NET Framework 4.5.1, referencing Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration packages from ASP.NET 5 RC1. (Go to gitHub.com/IntelliTect/Articles for the source code.)

The configuration API supports configuration providers for in-memory .NET objects, INI files, JSON files, XML files, command-line arguments, environment variables, an encrypted user store, and any custom provider you create. If you wish to leverage JSON files for your configuration, just add the Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.Json NuGet package. Then, if you want to allow the command line to provide configuration information, simply add the Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.CommandLine NuGet package, either in addition to or instead of other configuration references. If none of the built-in configuration providers are satisfactory, you’re free to create your own by implementing the interfaces found in Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.Abstractions.

Retrieving Configuration Settings

To familiarize yourself with retrieving configuration settings, take a look at Figure 1.

Figure 1. Configuration Basics Using the InMemoryConfigurationProvider and ConfigurationBinder Extension Methods

public class Program

{

static public string DefaultConnectionString { get; } =

@"Server=(localdb)\\mssqllocaldb;Database=SampleData-0B3B0919-C8B3-481C-9833-

36C21776A565;Trusted_Connection=True;MultipleActiveResultSets=true";

static IReadOnlyDictionary<string, string> DefaultConfigurationStrings{get;} =

new Dictionary<string, string>()

{

["Profile:UserName"] = Environment.UserName,

[$"AppConfiguration:ConnectionString"] = DefaultConnectionString,

[$"AppConfiguration:MainWindow:Height"] = "400",

[$"AppConfiguration:MainWindow:Width"] = "600",

[$"AppConfiguration:MainWindow:Top"] = "0",

[$"AppConfiguration:MainWindow:Left"] = "0",

};

static public IConfiguration Configuration { get; set; }

public static void Main(string[] args = null)

{

ConfigurationBuilder configurationBuilder =

new ConfigurationBuilder();

// Add defaultConfigurationStrings

configurationBuilder.AddInMemoryCollection(

DefaultConfigurationStrings);

Configuration = configurationBuilder.Build();

Console.WriteLine($"Hello {Configuration["Profile:UserName"]}");

ConsoleWindow consoleWindow =

Configuration.Get<ConsoleWindow>("AppConfiguration:MainWindow");

ConsoleWindow.SetConsoleWindow(consoleWindow);

}

}Accessing the configuration begins easily with an instance of the ConfigurationBuilder, a class available from the Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration NuGet package. Given the ConfigurationBuilder instance, you can add providers directly using IConfigurationBuilder extension methods like AddInMemoryCollection, as shown in Figure 1. This method takes a Dictionary<string,string> instance of the configuration name-value pairs, which it uses to initialize the configuration provider before adding it to the ConifigurationBuilder instance. Once the configuration builder is “configured,” you invoke its Build method to retrieve the configuration.

As mentioned earlier, a configuration is simply a hierarchical list of name-value pairs in which the nodes are separated by a colon. Therefore, to retrieve a particular value, you simply access the Configuration indexer with the corresponding item’s key:

Console.WriteLine($"Hello {Configuration["Profile:UserName"]}");However, accessing a value isn’t limited to only retrieving strings. You can, for example, retrieve values via the ConfigurationBinder’s Get

Configuration.Get<int>("AppConfiguration:MainWindow:ScreenBufferSize", 80);This binding support requires a reference to the Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.Binder NuGet package.

Notice there’s an optional argument following the key, for which you can specify a default value to return when the key doesn’t exist. (Without the default value, the return will be assigned default(T), rather than throw an exception as you might expect.)

Configuration values are not limited to scalars. You can retrieve POCO objects or even entire object graphs. To retrieve an instance of the ConsoleWindow whose members map to the AppConfiguration:MainWindow configuration section, Figure 1 uses:

ConsoleWindow consoleWindow =

Configuration.Get<ConsoleWindow>("AppConfiguration:MainWindow")Alternatively, you could define a configuration graph such as AppConfiguration, shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. A Sample Configuration Object Graph

class AppConfiguration

{

public ProfileConfiguration Profile { get; set; }

public string ConnectionString { get; set; }

public WindowConfiguration MainWindow { get; set; }

public class WindowConfiguration

{

public int Height { get; set; }

public int Width { get; set; }

public int Left { get; set; }

public int Top { get; set; }

}

public class ProfileConfiguration

{

public string UserName { get; set; }

}

}

public static void Main()

{

// ...

AppConfiguration appConfiguration =

Program.Configuration.Get<AppConfiguration>(

nameof(AppConfiguration));

// Requires referencing System.Diagnostics.TraceSource in Corefx

System.Diagnostics.Trace.Assert(

600 == appConfiguration.MainWindow.Width);

}With such an object graph, you could define all or part of your configuration with a strongly typed object hierarchy that you can then use to retrieve your settings all at once.

Multiple Configuration Providers

The InMemoryConfigurationProvider is effective for storing default values or possibly calculated values. However, with only that provider, you’re left with the burden of retrieving the configuration and loading it into a Dictionary<string,string> before registering it with the ConfigurationBuilder. Fortunately, there are several more built-in configuration providers, including three file-based providers (XmlConfigurationProvider, IniConfigurationProvider and JsonConfigurationProvider); an environment variable provider (EnvironmentVariableConfigurationProvider); and a command-line argument provider (CommandLineConfigurationProvider). Furthermore, these providers can be mixed and matched to suit your application logic. Imagine, for example, that you might specify configuration settings in the following ascending priority:

- InMemoryConfigurationProvider

- JsonFileConfigurationProvider for Config.json

- JsonFileConfigurationProvider for Config.Production.json

- EnvironmentVariableConfigurationProvider

- CommandLineConfigurationProvider

In other words, the default configuration values might be stored in code. Next, the config.json file followed by the Config.Production.json might override the InMemory specified values—where later providers like the JSON ones take precedence for any overlapping values. Next, when deploying, you may have custom configuration values stored in environment variables. For example, rather than hardcoding Config.Production.json, you might retrieve the environment setting from a Windows environment variable and access the specific file (perhaps Config.Test.Json) that the environment variable identifies. (Excuse the ambiguity in the term environment setting relating to production, test, pre-production or development, versus Windows environment variables such as %USERNAME% or %USERDOMAIN%.) Finally, you specify (or override) any earlier provided settings via the command line—perhaps as a onetime change to, for example, turn on logging.

To specify each of the providers, add them to the configuration builder (via the extension method AddX fluent API), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Adding Multiple Configuration Providers—the Last One Specified Takes Precedence

public static void Main(string[] args = null)

{

ConfigurationBuilder configurationBuilder =

new ConfigurationBuilder();

configurationBuilder

.AddInMemoryCollection(DefaultConfigurationStrings)

.AddJsonFile("Config.json",

true) // Bool indicates file is optional

// "EssentialDotNetConfiguartion" is an optional prefix for all

// environment configuration keys, but once used,

// only environment variables with that prefix will be found

.AddEnvironmentVariables("EssentialDotNetConfiguration")

.AddCommandLine(

args, GetSwitchMappings(DefaultConfigurationStrings));

Console.WriteLine($"Hello {Configuration["Profile:UserName"]}");

AppConfiguration appConfiguration =

Configuration.Get<AppConfiguration>(nameof(AppConfiguration));

}

static public Dictionary<string,string> GetSwitchMappings(

IReadOnlyDictionary<string, string> configurationStrings)

{

return configurationStrings.Select(item =>

new KeyValuePair<string, string>(

"-" + item.Key.Substring(item.Key.LastIndexOf(':')+1),

item.Key))

.ToDictionary(

item => item.Key, item=>item.Value);

}For the JsonConfigurationProvider, you can either require the file to exist or make it optional; hence the additional optional parameter on AddJsonFile. If no parameter is provided, the file is required and a System.IO.FileNotFoundException will fire if it isn’t found. Given the hierarchical nature of JSON, the configuration fits very well into the configuration API (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. JSON Configuration Data for the JsonConfigurationProvider

{

"AppConfiguration": {

"MainWindow": {

"Height": "400",

"Width": "600",

"Top": "0",

"Left": "0"

},

"ConnectionString":

"Server=(localdb)\\\\mssqllocaldb;Database=Database-0B3B0919-C8B3-481C-9833-

36C21776A565;Trusted_Connection=True;MultipleActiveResultSets=true"

}

}The CommandLineConfigurationProvider requires you to specify the arguments when it’s registered with the configuration builder. Arguments are specified by a string array of name-value pairs, with each pair of the format /

["-DBConnectionString"]="AppConfiguration:ConnectionString",

["-LogFile"]="AppConfiguration:LogFile"Before finishing off the configuration basics, here are a few additional points to note:

- The CommandLineConfigurationProvider has several characteristics that are not intuitive from IntelliSense of which you need to be aware:

- The CommandLineConfigurationProvider’s switchMappings only allows a switch prefix of – or –. Even a slash (/) isn’t allowed as a switch parameter. This prevents you from providing aliases for slash switches via switch mappings.

- CommandLineConfigurationProviders doesn’t allow for switch-based command-line arguments—arguments that don’t include an assigned value. Specifying a key of “/Maximize,” for example, isn’t allowed.

- While you can pass Main’s args to a new CommandLineConfigurationProvider instance, you can’t pass Environment.GetCommandLineArgs without first removing the process name. (Note that Environment.GetCommandLineArgs behaves differently when a debugger is attached. Specifically, executable names with spaces are split into individual arguments when there’s no debugger attached.

- An exception will be issued when you specify a command-line switch prefix of – or — for which there’s no corresponding switch mapping.

- Although configurations can be updated (Configuration["Profile:UserName"]="Inigo Montoya"), the updated value is not persisted back into the original store. For example, when you assign a JSON provider configuration value, the JSON file won’t be updated. Similarly, an environment variable wouldn’t get updated when its configuration item is assigned.

- The EnvironmentVariableConfigurationProvider optionally allows for a key prefix to be specified. In such cases, it will load only those environment variables with the specified prefix. In this way, you can automatically limit the configuration entries to those within an environment variable “section” or, more broadly, those that are relevant to your application.

- Environment variables with a colon delimiter are supported. For example, assigning SET AppConfiguration:ConnectionString=Console on the command line is allowed.

- All configuration keys (names) are case-insensitive.

- Each provider is located in its own NuGet package where the NuGet package name corresponds to the provider: Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.CommandLine, Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.EnvironmentVariables, Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.Ini, Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.Json and Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.Xml.

Understanding the Object-Oriented Structure

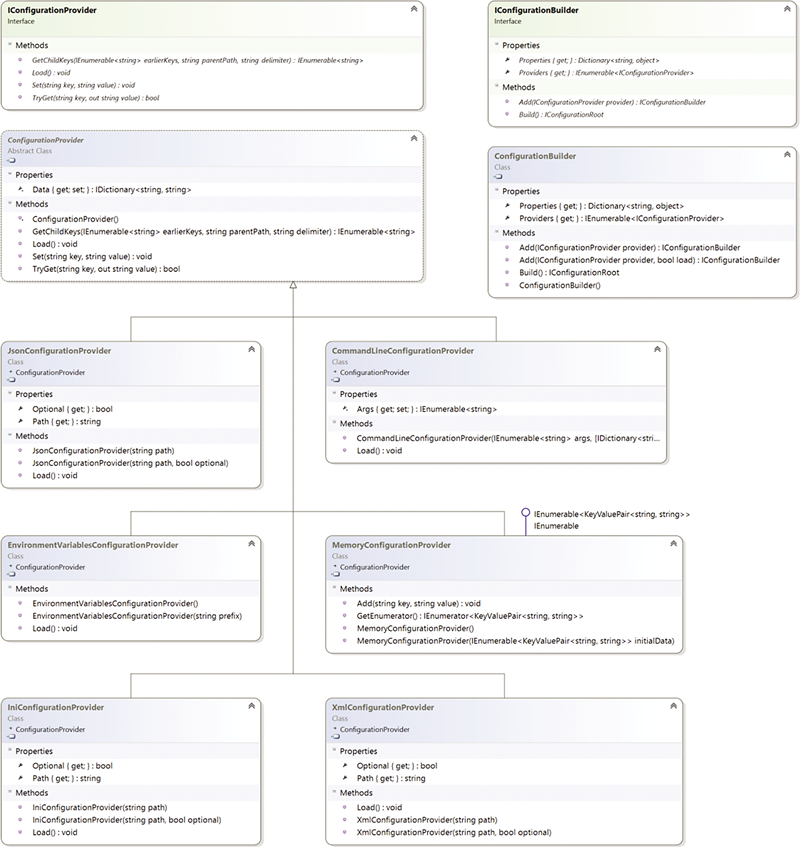

Both the modularity and the object-oriented structure of the configuration API are well thought out—providing discoverable, modular and easily extensible classes and interfaces with which to work (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Configuration Provider Class Model

Each type of configuration mechanism has a corresponding configuration provider class that implements IConfigurationProvider. In the majority of built-in provider implementations, the implementation is jump-started by deriving from ConfigurationBuilder rather than using custom implementations for all of the interface methods. Perhaps surprisingly, there’s no direct reference to any of the providers in Figure 1. This is because instead of manually instantiating each provider and registering it with the ConfigurationBuilder class’s Add method, each provider’s NuGet package includes a static extension class with IConfigurationBuilder extension methods. (The name of the extension class is generally identified by the suffix ConfigurationExtensions.) With the extension classes, you can start accessing the configuration data directly from ConfigurationBuilder (which implements IConfigurationBuilder) and directly call the extension method associated with your provider. For example, the JasonConfigurationExtensions class adds AddJsonFile extension methods to IConfigurationBuilder so that you can add the JSON configuration with a call to ConfigurationBuilder.AddJsonFile(fileName, optional).Build();.

For the most part, once you have a configuration, you have all you need to start retrieving values.

IConfiguration includes a string indexer, allowing you to retrieve any particular configuration value using the key to access the element for which you’re looking. You can retrieve an entire set of settings (called a section) with the GetSection or GetChildren methods (depending on whether you want to drill down an additional level in the hierarchy). Note that configuration element sections allow you to retrieve the following:

- key: the last element of the name.

- path: the full name pointing from the root to the current location.

- value: the configuration value stored in the configuration setting.

- value as an object: via the ConfigurationBinder, you can retrieve a POCO object that corresponds to the configuration section you’re accessing (and potentially its children). This is how the Configuration.Get

(nameof(AppConfiguration)) works in Figure 3, for example. - IConfigurationRoot includes a Reload function that allows you to reload values in order to update the configuration. ConfigurationRoot (which implements IConfigurationRoot) includes a GetReloadToken method that lets you register for notifications of when a reload occurs (and the value might change).

Encrypted Settings

On occasion, you’ll want to retrieve settings that are encrypted rather than stored in open text. This is important, for example, when you’re storing OAuth application keys or tokens or storing credentials for a database connection string. Fortunately, the Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration system has built-in support for reading encrypted values. To access the secure store, you need to add a reference to the Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.UserSecrets NuGet package. Once it’s added, you’ll have a new IConfigurationBuilder.AddUserSecrets extension method that takes a configuration item string argument called userSecretsId (stored in your project.json file). As you’d expect, once the UserSecrets configuration is added to your configuration builder, you can begin retrieving encrypted values, which only users with whom the settings are associated can access.

Obviously, retrieving settings is somewhat pointless if you can’t also set them. To do this, use the user-secret.cmd tool as follows:

user-secret set <secretName> <value> [--project <projectPath>]The –project option allows you to associate the setting with the userSecretsId value stored in your project.json file (created by default by the ASP.NET 5 new project wizard). If you don’t have the user-secret tool, you’ll need to add it via the developer command prompt using the DNX utility (currently dnu.exe).

For more information on the user secret configuration option, see the article, “Safe Storage of Application Secrets,” by Rick Anderson and David Roth at bit.ly/1mmnG0L.

Wrapping Up

Those of you who have been with .NET for some time have likely been disappointed with the built-in support for configuration via System.Configuration. This is probably especially true if you’re coming from classic ASP.NET, where configuration was limited to Web.Config or App.config files and then only by accessing the AppSettings node within that. Fortunately, the new open source Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration API goes well beyond what was originally available by adding a multitude of new configuration providers, along with an easily extensible system into which you can plug any custom provider you want. For those still living (stuck?) in a pre-ASP.NET 5 world, the old System.Configuration APIs still function, but you can slowly begin to migrate (even side-by-side) to the new API just by referencing the new packages. Furthermore, the NuGet packages can be used from Windows client projects like console and Windows Presentation Foundation applications. Therefore, the next time you need to access configuration data, there’s little reason not to leverage the Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration API.

Thanks to the following IntelliTect technical experts for reviewing this article: Grant Erickson.

This article was originally posted here in the February 2016 issue of MSDN Magazine.

</string,string></string,string></string,string>