If you’ve spent any time around modern AI systems this past year, you’ve probably heard some version of this idea – if one agent is good, more agents must be better. The thinking goes:

Need better reasoning? Add agents.

Need reliability? Add agents.

Need scale? Definitely add agents.

A recent paper, “Towards a Science of Scaling Agent Systems” (December 2025), puts that assumption to the test in a way that feels refreshingly grounded. Instead of showcasing clever demos, the researchers ran a controlled evaluation across 180 configurations to answer a very practical question: when does adding agents actually improve performance, and when does it get in the way?

To keep the comparison fair, they held constant the things that usually muddy these discussions:

- Three major model families were evaluated (GPT-5, Gemini 2.x, and Claude 3.7/4.5)

- Tools, prompt structure, and total token budgets were standardized

- Both single-agent and multi-agent systems were tested on the same tasks

What emerged wasn’t a blanket endorsement, or rejection for that matter, of multi-agent systems, but a much more nuanced picture.

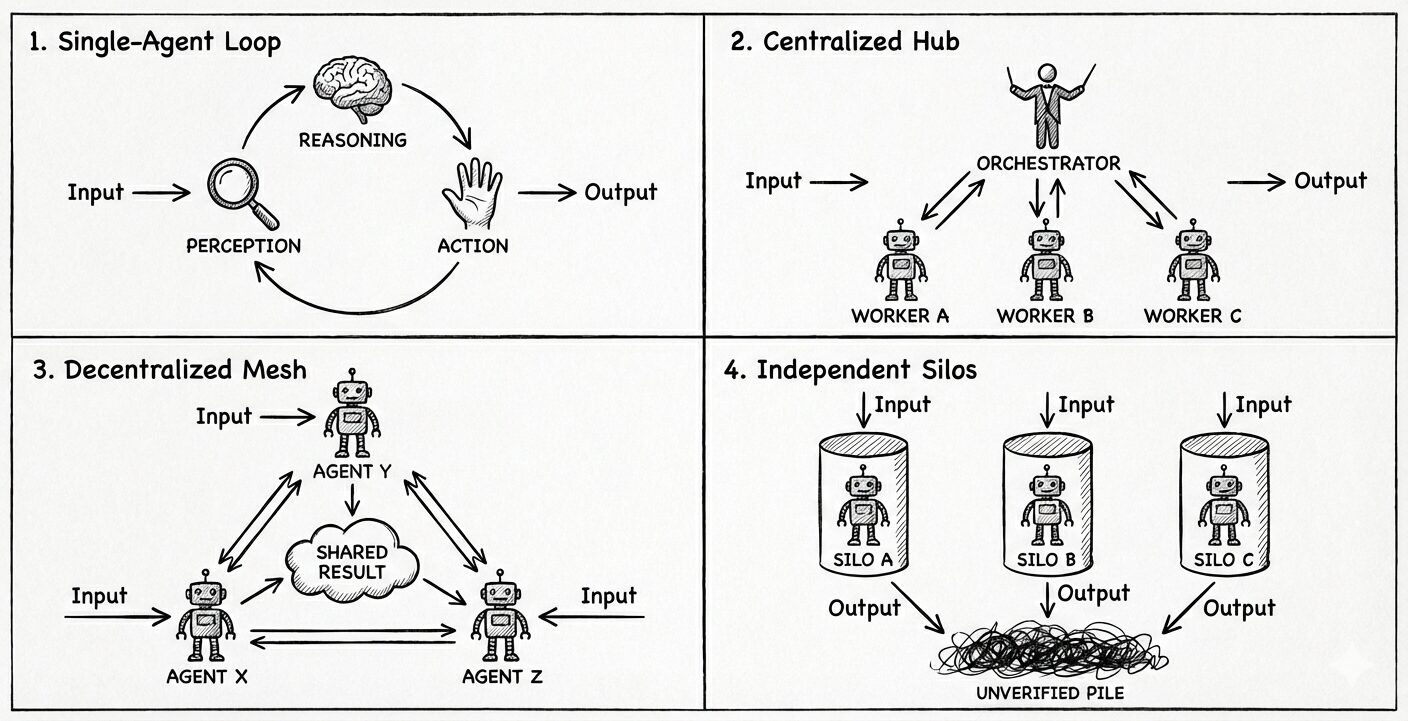

Not All Agent Architectures Are Created Equal

The paper evaluated several common patterns we see in real-world systems today:

- Single-Agent Systems (SAS), where one agent handles perception, reasoning, and action in a single loop

- Centralized multi-agent systems, where a central orchestrator delegates work and synthesizes results

- Decentralized systems, where agents communicate peer-to-peer to reach consensus

- Independent agents, which work in parallel without communicating at all

Each of these has strengths, but only when matched to the right kind of task.

Where Multiple Agents Help and Where They Hurt

The clearest wins for multi-agent systems showed up in problems that are naturally parallel. In a structured financial reasoning task, a centralized multi-agent system outperformed a single agent by more than 80%. When work can be cleanly decomposed and verified, delegation pays off.

But as tasks became more sequential or constraint-heavy, performance dropped sharply. In a planning benchmark where each step depended tightly on the last, multi-agent systems consistently underperformed single agents, sometimes by as much as 50–70%. Coordination overhead consumed valuable context, interrupted reasoning chains, and introduced subtle inconsistencies that compounded over time. No bueno.

Tool-heavy workflows told a similar story. While you might expect multiple agents to help manage complexity, the gains were marginal. Tool usage already demands careful reasoning and context management, and adding coordination on top often reduced the “cognitive budget” available for the actual work.

A particularly important finding was how errors propagated:

- Independent agents amplified errors dramatically, with mistakes compounding more than 17× (Oof!)

- Centralized systems contained that amplification to roughly 4×, largely because an orchestrator could verify and correct outputs

In other words, parallelism without oversight isn’t just unhelpful, it’s actively dangerous in production settings.

A Practical Rule of Thumb

One of the most useful contributions of the paper is a simple selection rule that aligns closely with what we see in practice:

- Centralized multi-agent systems work best for parallelizable, structured tasks like financial analysis

- Decentralized systems can help with exploration-heavy work such as open-ended research

- Single-agent systems are often the right choice for sequential, tool-intensive, or constraint-driven workflows

Another key insight is what the authors call capability saturation. Once a single agent is already performing reasonably well, adding more agents often introduces noise rather than insight. More voices don’t automatically mean better judgment.

What This Means for Real Systems

For teams building AI systems that need to be reliable, explainable, and maintainable, the message here is not “don’t use multi-agent systems.” It’s “use them intentionally.”

At IntelliTect, we’ve learned that the hardest architectural decisions often involve restraint. A single, well-structured agent with clear responsibilities and strong guardrails can outperform a complex web of agents, especially when the task demands continuity and precision.

As AI models continue to improve, the real mark of good system design may be how little complexity you need to introduce to get the job done well. That doesn’t make for flashy demos, but it’s what leads to systems clients can trust and developers can confidently support.

Do you want to become a “Frontier Firm” and better use AI?

Let’s chat about how we can help you innovate!