Background

Back in November, in the Connect() special issue of MSDN Magazine, I provided an overview of C# 7.0 in which I introduced tuples. Click here for the overview. In this blog I delve into tuples again, covering the full breadth of the syntax options.

Why Tuples?

On occasion, you’ll likely find it useful to combine data elements. Suppose, for example, you’re working with information about countries, such as the poorest country in the world in 2017: Malawi, whose capital is Lilongwe, with a GDP per capita of $226.50. You could obviously declare a class for this data, but it doesn’t really represent your typical noun/object. It’s seemingly more a collection of related pieces of data than it is an object. Surely, if you were going to have a Country object, for example, it would have considerably more data than just properties for the Name, Capital, and GDP per Capita. Alternatively, you could store each data element in individual variables, but the result would be no association between the data elements; $226.50 would have no association with Malawi except perhaps by a common suffix or prefix in the variable names. Another option would be to combine all the data into a single string—with the disadvantage that to work with each data element individually would require parsing it out. A final approach might be to create an anonymous type, but that too has limitations; enough, in fact, that tuples could potentially replace anonymous types entirely. We’ll leave this topic until the end of the blog.

The best option might be the C# 7.0 tuple, which, at its simplest, provides a syntax that allows you to combine the assignment of multiple variables, of varying types, in a single statement:

(string country, string capital, double gdpPerCapita) =

("Malawi", "Lilongwe", 226.50);In this case, I’m not only assigning multiple variables but declaring them as well.

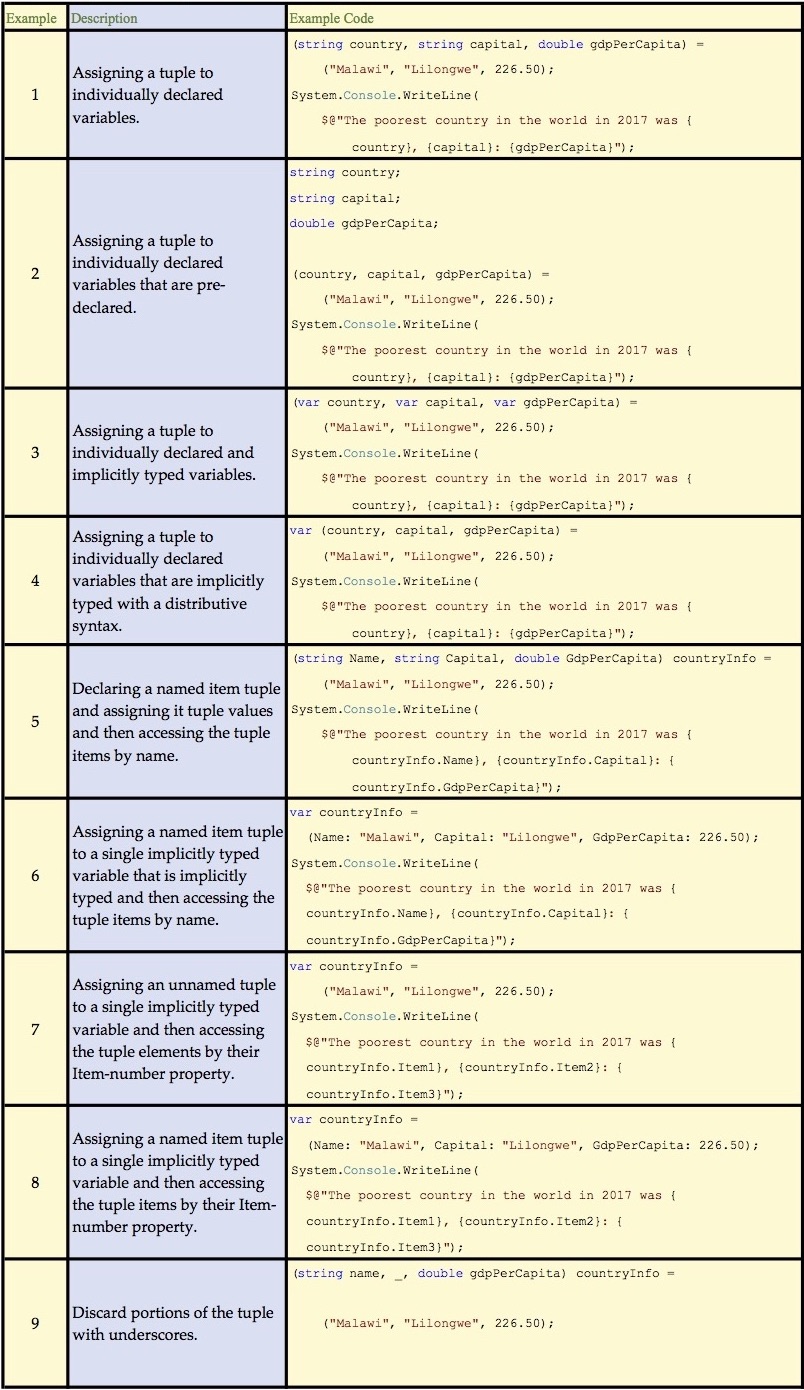

However, tuples have several other additional syntax possibilities, each shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Sample Code for Tuple Declaration and Assignment

In the first four examples, and although the right-hand side represents a tuple, the left-hand side still represents individual variables that are assigned together using tuple syntax, which involves two or more elements separated by commas and associated with parentheses. (I use the term tuple syntax because the underlying data type the compiler generates on the left-hand side isn’t technically a tuple.) The result is that although I start with values combined as a tuple on the right, the assignment to the left deconstructs the tuple into its constituent parts. In example 2, the left-hand-side assignment is to pre-declared variables. However, in examples 1, 3, and 4, the variables are declared within the tuple syntax. Given that I’m only declaring variables, the naming and casing convention follows the generally accepted Framework Design Guidelines—"DO use camelCase for local variable names," for example.

Note that although implicit typing (var) can be distributed across each variable declaration within the tuple syntax, as shown in example 4, you can’t do the same with an explicit type (such as string). Since tuples allow each item to be a different data type, distributing the explicit type name across all elements wouldn’t necessarily work unless all the item data types were identical (and even then, the compiler doesn’t allow it).

In example 5, I declare a tuple on the left-hand side and then assign the tuple on the right. Note that the tuple has named items—names you can then reference to retrieve the item values back out of the tuple. This is what enables the countryInfo.Name, countryInfo.Capital, and countryInfo.GdpPerCapita syntax in the System.Console.WriteLine statement. The result of the tuple declaration on the left is a grouping of the variables into a single variable (countryInfo) from which you can then access the constituent parts. This is useful because you can then pass this single variable around to other methods and those methods will also be able to access the individual items within the tuple.

As already mentioned, variables defined using tuple syntax use camelCase. However, the convention for tuple item names is not well defined. Suggestions include using parameter naming conventions when the tuple behaves like a parameter – such as when returning multiple values that before tuple syntax would have used out parameters. The alternative is to use PascalCase – following the naming convention for public fields and properties. I strongly favor the later approach in accordance with the Capitalization Rules for Identifiers (itl.tc/caprfi). Tuple item names are rendered as members of the tuple, and the convention for all (public) members (which are potentially accessed using a dot operator) is PascalCase.

Tuple Naming Guidelines:

DO use camelCase for all variables declared using tuple syntax.

CONSIDER using PascalCase for all tuple items’ names.

Example 6 provides the same functionality as example 5, although it uses named tuple items on the right-hand side tuple value and an implicit type declaration on the left. The items’ names are persisted to the implicitly typed variable, however, so they’re still available for the WriteLine statement. Of course, this opens the possibility that you could name the items on the left-hand side with names that are different from those you use on the right. While the C# compiler allows this, it will issue a warning that the item names on the right will be ignored as those on the left take precedence.

If no item names are specified, the individual elements are still available from the assigned tuple variable. However, the names are Item1, Item2, and so on, as shown in example 7. In fact, the ItemX name is always available on the tuple—even when custom names are provided (see example 8). However, when using IDE tools like any of the recent flavors of Visual Studio that support C# 7.0, the ItemX property will not appear within the IntelliSense dropdown—a good thing since presumably the provided name is preferable.

As shown in example 9, portions of a tuple assignment can be excluded using an underscore; this is called a discard.

Tuples are a lightweight solution for encapsulating data into a single object in the same way that a bag might capture miscellaneous items you pick up from the store. Unlike arrays, tuples contain item data types that can vary virtually without constraint (pointers aren’t allowed), except that they’re identified by the code and can’t be changed at runtime. Also, unlike with arrays, the number of items within the tuple is hard-coded at compile time as well. Lastly, you can’t add custom behavior to a tuple (extension methods notwithstanding). If you need behavior associated with the encapsulated data, then leveraging object-oriented programing and defining a class is the preferred approach.

The System.ValueTuple<…> Type

The C# compiler generates code that relies on a set of generic value types (structs), such as System.ValueTuple<T1, T2, T3>, as the underlying implementation for the tuple syntax for all tuple instances on the right-hand side of the examples in Figure 1. Similarly, the same set of System.ValueTuple<...> generic value types is used for the left-hand-side data type starting with example 5. As you’d expect with a tuple type, the only methods included are those related to comparison and equality. However, perhaps unexpectedly, there are no properties for ItemX but rather read-write fields (seemingly breaking the most basic of .NET Programming Guidelines as explained at itl.tc/CS7TuplesBreaksGuidelines).

In addition to the programming guidelines discrepancy, there’s another behavioral question that arises. Given that the custom item names and their types aren’t included in the System.ValueTuple<...> definition, how is it possible that each custom item name is seemingly a member of the System.ValueTuple<...> type and accessible as a member of that type?

What’s surprising (particularly for those familiar with the anonymous type implementation) is that the compiler doesn’t generate underlying CIL code for the members corresponding to the custom names. However, even without an underlying member with the custom name, there is (seemingly) from the C# perspective, such a member.

For all the named tuple local variable examples, for example:

var countryInfo = (Name: "Malawi", Capital: "Lilongwe", GdpPerCapita: 226.50)it’s clearly possible that the names could be known by the compiler for the remainder of the scope of the tuple since that scope is bounded within the member in which it’s declared. And, in fact, the compiler (and IDE) quite simply rely on this scope to allow accessing each item by name. In other words, the compiler looks at the item names within the tuple declaration and leverages them to allow code that uses those names within the scope. It is for this reason as well that the ItemX methods are not shown in the IDE IntelliSense as available members on the tuple (the IDE simply ignores them and replaces them with the named items).

Determining the item names from when scoped within a member is reasonable for the compiler, but what happens when a tuple is exposed outside the member—such as a parameter or return from a method that’s in a different assembly (for which there is possibly no source code available)? For all tuples that are part of the API (whether a public or private API), the compiler adds item names to the metadata of the member in the form of attributes. For example, this:

[return: System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TupleElementNames(

new string[] {"First", "Second"})]

public System.ValueTuple<string, string> ParseNames(string fullName)

{

// ...

}is the C# equivalent of what the compiler generates for the following:

public (string First, string Second) ParseNames(string fullName)On a related note, C# 7.0 does not enable the use of custom item names when using the explicit System.ValueTuple<…> data type. Therefore, if you replace var in Example 8 of Figure 1, you’ll end up with warnings that each item name will be ignored.Here are a few additional miscellaneous facts to keep in mind about

Here are a few additional miscellaneous facts to keep in mind about System.ValueTuple<…>.

- There are a total of eight generic

System.ValueTuplestructs corresponding to the possibility of supporting a tuple with up to seven items. For the eighth tuple,System.ValueTuple<T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6, T7, TRest>, the last type parameter allows specifying an additional value tuple, thus enabling support for n items. If, for example, you specify a tuple with eight parameters, the compiler will automatically generate aSystem.ValueTuple<T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6, T7,System.ValueTuple<TSub1>>as the underlying implementing type. (For completeness,System.Value<T1>exists but will really only be used directly and only as a type. It will never be used directly by the compiler since the C# tuple syntax requires a minimum of two items.) - There is a non-generic

System.ValueTuplethat serves as a tuple factory with Create methods corresponding to each value tuple rarity. The ease of using a tuple literal, such as var t1 = (“Inigo Montoya”, 42), supersedes the Create method at least for C# 7.0 (or later) programmers. - For all practical purposes, C# developers can essentially ignore

System.ValueTupleandSystem.ValueTuple<T>.

There’s another tuple type that was included with the .NET Framework 4.5—System.Tuple<…>. At that time, it was expected to be the core tuple implementation going forward. However, once C# supported tuple syntax, it was realized that a value type was generally more performant and so System.ValueTuple<…> was introduced, effectively replacing System.Tuple<…> in all cases except for backward compatibility with existing APIs that depend on System.Tuple<…>.

Wrapping Up

What many folks didn’t realize when it was first introduced is that the new C# 7.0 tuple all but replaces anonymous types—and provides additional functionality. Tuples can be returned from methods, for example, and the item names are persisted in the API such that meaningful names can be used in place of ItemX type naming. And, like anonymous types, tuples can even represent complex hierarchical structures such as those that might be constructed in more complex LINQ queries (albeit, like with anonymous types, developers should do this with caution). That said, this could possibly lead to situations where the tuple value type exceeds 128 bytes and, therefore, might be a corner case for when to use anonymous types because it’s a reference type. Except for these corner cases (accessing via typical reflection might be another example), there’s little to no reason to use an anonymous type when programming with C# 7.0 or later.

The ability to program with a tuple type object has been around for a long time (as mentioned, a tuple class, System.Tuple<…>, was introduced with .NET Framework 4, but was available in Silverlight before that). However, these solutions never had an accompanying C# syntax, but rather nothing more than a .NET API. C# 7.0 brings a first-class tuple syntax that enables literals—like var tuple = (42, "Inigo Montoya")—implicit typing, strong typing, public API utilization, integrated IDE support for named ItemX data, and more. Admittedly, it might not be something you use in every C# file, but it’s likely something you’ll be grateful to have when the need arises, and you’ll welcome the tuple syntax over the alternative out parameter or anonymous type.

Much of this post derives from my Essential C# book (/innovative-products/essential-csharp-book/), which I am currently in the midst of updating to Essential C# 7.0. For more information on this topic, check out Chapter 3.

Thanks to the following Microsoft technical expert for reviewing this blog: Mads Torgersen (https://twitter.com/MadsTorgersen).

This article was originally posted here in the August 2017 issue of MSDN Magazine.

Comments are closed.