Exploring foreach loops

Many moons ago I discussed the foreach loop. I expand on that post here as I continue my series for the MSDN C# Developer Center.

The advantage of a foreach loop over a for loop is the fact that it is unnecessary to know the number of items within the collection when an iteration starts. This avoids iterating off the end of the collection using an index that is not available. One important advantage of a foreach loop is that it allows code to iterate over a collection without first loading the collection in entirety into memory. In this article I am going to explore how the foreach statement works under the covers. This sets the stage for a follow on discussion of how the yield statement works.

foreach

foreach Consider the foreach code listing shown in Listing 1:

Listing 1: foreach

int[] array = new int[]{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6};

foreach(int item in array)

{

Console.WriteLine(item);

} From this code, the C# compiler creates CIL equivalent of a for loop like this (Listing 2):

Listing 2: Compiled Implementation of foreach with Arrays

int[] tempArray;

int[] array = new int[] {

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6

};

tempArray = array;

for (int counter = 0;

(counter<tempArray.Length); counter++) {

readonly int item = tempArray[counter];

Console.WriteLine(item);

}Since the collection is an array and indexing the array is fast, the foreach loop implementation relies on support for the Length property and the index operator ([]). However, these two array features are not available on all collections. Many collections do not have a known number of elements and many collection classes do not support retrieving elements by index.

foreach with IEnumerable

To address this, the foreach loop uses the System.Collections.Generic.IEnumerator<T> <code>. (Given C# 2.0's generics support, there is very little reason to consider using the non-generic equivalent collections so I will ignore them from this discussion except to say their behavior is almost identical.) </code> IEnumerator<T> <code> is designed to enable the iterator pattern for iterating over collections of elements, rather than the length-index pattern shown in earlier. </code> IEnumerator<T> <code> includes three members. The first is bool </code> MoveNext()

Listing 3: Iterating over a collection using while

System.Collections.Generic.Stack<int>stack = new System.Collections.Generic.Stack<int>();

int number;

// ...

// This code is conceptual, not that the actual code.

while (stack.MoveNext()) {

number = stack.Current;

Console.WriteLine(number);

}The MoveNext() <code> method in this listing returns false when it moves past the end of the collection. This replaces the need to count elements while looping. (The last member on </code> IEnumerator<T> <code>, </code> Reset()

Interleaving

The problem with is that if there are two (or more) interleaving loops over the same collection, one foreach inside another, then the collection must maintain a state indicator of the current element so that when MoveNext()

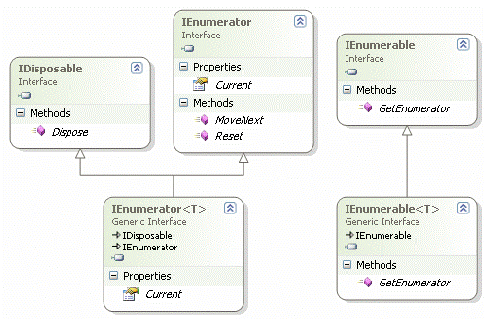

Figure 1. IEnumerable

To overcome this problem, the IEnumerator<T> <code> interfaces are not supported by the collection classes directly. As shown in Figure 1, there is a second interface called </code> IEnumerable<T> <code> whose only method is </code> GetEnumerator() <code>. The purpose of this method is to return an object that supports </code> IEnumerator<T> <code>. Rather than the collection class maintaining the state itself, a different class, usually a nested class so that it has access to the internals of the collection, will support the </code> IEnumerator<T>

Listing 4: A separate enumerator maintains state during an iteration

System.Collections.Generic.Stack<int>stack = new System.Collections.Generic.Stack<int>();

int number;

System.Collections.Generic.Stack<int>.IEnumerator<int>enumerator;

// ...

// If IEnumerable<T> is implemented explicitly,

// then a cast is required.

// ((IEnumerable)stack).GetEnumeraor();

enumerator = stack.GetEnumerator();

while (enumerator.MoveNext()) {

number = en umerator.Current;

Console.WriteLine(number);

}Error Handling

Since the classes that implement the IEnumerator<T> <code> interface maintain the state, there are occasions when the state needs cleaning up after all iterations have completed. To achieve this, the </code> IEnumerator<T> <code> interface derives from </code> IDisposable <code>. Enumerators that implement </code> IEnumerator <code> do not necessarily implement </code> IDisposable <code>, but if they do, </code> Dispose() <code> will be called as well. This enables the calling of </code> Dispose()

Listing 5: Compiled Result of foreach on Collections

System.Collections.Generic.Stack<intstack> = new System.Collections.Generic.Stack<int>();

int number;

System.Collections.Generic.Stack<int>.Enumerator<int enumerator;

IDisposable disposable;

enumerator = stack.GetEnumerator();

try {

while (enumerator.MoveNext()) {

number = enumerator.Current;

Console.WriteLine(number);

}

} finally {

// Explicit cast used for IEnumerator<T>.

disposable = (IDisposable) enumerator;

disposable.Dispose();

// IEnumerator will use the as operator unless IDisposable

// support determinable at compile time.

// disposable = (enumerator as IDisposable);

// if (disposable != null)

// {

// disposable.Dispose();

// }

}Notice that because the IDisposable <code> interface is supported by </code> IEnumerator<T>

Listing 6: Error handling and resource cleanup with using

System.Collections.Generic.Stack<intstack>= new System.Collections.Generic.Stack<int>();

int number;

using(System.Collections.Generic.Stack<int> .Enumerator<int> enumerator = stack.GetEnumerator()) {

while (enumerator.MoveNext()) {

number = enumerator.Current;

Console.WriteLine(number);

}

}However, recall that the using keyword is not directly supported by CIL either, so in reality the former code is a more accurate C# representation of the foreach CIL code.

Readers may recall that the compiler prevents assignment of the foreach <code> variable identifier (</code> number

In addition, the element count within a collection cannot be modified during the execution of a foreach <code> loop. If, for example, we called </code> stack.Push(42) <code> inside the </code> foreach

Because of this ambiguity, an exception of type System.InvalidOperationException <code> is thrown if the collection is modified within a </code> foreach

(This content was largely taken from the Collections chapter of my book, Essential C# 2.0 [Addison-Wesley])

Comments are closed.