Efficiently Code Using C# 6.0

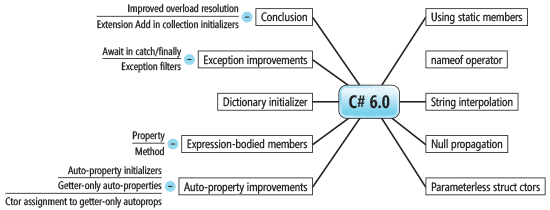

C# 6.0 isn’t a radical revolution in C# programming. Unlike the introduction of generics in C# 2.0, C# 3.0 and its groundbreaking way to program collections with LlNQ, or the simplification of asynchronous programming patterns in C# 5.0, C# 6.0 isn’t going to transform development. That said, C# 6.0 will change the way you write C# code in specific scenarios, due to features that are so much more efficient you’ll likely forget there was another way to code them. It introduces new syntax shortcuts, reduces the amount of ceremony on occasion, and ultimately makes writing C# code leaner. In this article I’m going to delve into the details of the new C# 6.0 feature set that make all this possible. Specifically, I’ll focus on the items outlined in the Mind Map shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. C# 6.0 Mind Map

Note that many of the examples herein come from the next edition of my book, “Essential C# 6.0” (Addison-Wesley Professional).

Using Static

Many of the C# 6.0 features can be leveraged in the most basic of Console programs. For example, using is now supported on specific classes in a feature called the using static directive, which renders static methods available in global scope, without a type prefix of any kind, as shown in Figure 2. Because System.Console is a static class, it provides a great example of how this feature can be leveraged.

Figure 2. The Using Static Directive Reduces Noise Within Your Code

using System;

using static System.ConsoleColor;

using static System.IO.Directory;

using static System.Threading.Interlocked;

using static System.Threading.Tasks.Parallel;

public static class Program

{

// ...

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Parameter checking eliminated for elucidation.

EncryptFiles(args[0], args[1]);

}

public static int EncryptFiles(

string directoryPath, string searchPattern = "*")

{

ConsoleColor color = ForegroundColor;

int fileCount = 0;

try

{

ForegroundColor = Yellow

WriteLine("Start encryption...");

string[] files = GetFiles(directoryPath, searchPattern,

System.IO.SearchOption.AllDirectories);

ForegroundColor = White

ForEach(files, (filename) =>

{

Encrypt(filename);

WriteLine(" '{0}' encrypted", filename);

Increment(ref fileCount);

});

ForegroundColor = Yellow

WriteLine("Encryption completed");

}

finally

{

ForegroundColor = color;

}

return fileCount;

}

}In this example, there are using static directives for System.ConsoleColor, System.IO.Directory, System.Threading.Interlocked and System.Threading.Tasks.Parallel. These enable the invocation of numerous methods, properties and enums directly: ForegroundColor, WriteLine, GetFiles, Increment, Yellow, White and ForEach. In each case, this eliminates the need to qualify the static member with its type. (For those of you using Visual Studio 2015 Preview or earlier, the syntax doesn’t include adding the “static” keyword after using, so it’s only “using System.Console,” for example. In addition, not until after Visual Studio 2015 Preview does the using static directive work for enums and structs in addition to static classes.)

For the most part, eliminating the type qualifier doesn’t significantly reduce the clarity of the code, even though there is less code. WriteLine in a console program is fairly obvious as is the call to GetFiles. And, because the addition of the using static directive on System.Threading.Tasks.Parallel was obviously intentional, ForEach is a way of defining a parallel foreach loop that, with each version of C#, looks (if you squint just right) more and more like a C# foreach statement.

The obvious caution with the using static directive is to take care that clarity isn’t sacrificed. For example, consider the Encrypt function defined in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Ambiguous Exists Invocation (with the nameof Operator)

private static void Encrypt(string filename)

{

if (!Exists(filename)) // LOGIC ERROR: Using Directory rather than File

{

throw new ArgumentException("The file does not exist.",

nameof(filename));

}

// ...

}It would seem that the call to Exists is exactly what’s needed. However, more explicitly, the call is Directory.Exists when, in fact, File.Exists is what’s needed here. In other words, although the code is certainly readable, it’s incorrect and, at least in this case, avoiding the using static syntax is probably better.

Note that if using static directives are specified for both System.IO.Directory and System.IO.File, the compiler issues an error when calling Exists, forcing the code to be modified with a type disambiguation prefix in order to resolve the ambiguity.

An additional feature of the using static directive is its behavior with extension methods. Extension methods aren’t moved into global scope, as would happen with static methods normally. For example, a using static ParallelEnumerable directive would not put the Select method into global scope and you couldn’t call Select(files, (filename) => { … }). This restriction is by design. First, extension methods are intended to be rendered as instance methods on an object (files.Select((filename)=>{ … }) for example) and it’s not a normal pattern to call them as static methods directly off of the type. Second, there are libraries such as System.Linq, with types such as Enumerable and ParallelEnumerable that have overlapping method names like Select. To have all these types added to the global scope forces unnecessary clutter into IntelliSense and possibly introduces an ambiguous invocation (although not in the case of System.Linq-based classes).

Although extension methods won’t get placed into global scope, C# 6.0 still allows classes with extension methods in using static directives. The using static directive achieves the same as a using (namespace) directive does except only for the specific class targeted by the using static directive. In other words, using static allows the developer to narrow what extensions methods are available down to the particular class identified, rather than the entire namespace. For example, consider the snippet in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Only Extension Methods from ParallelEnumerable Are in Scope

using static System.Linq.ParallelEnumerable;

using static System.IO.Console;

using static System.Threading.Interlocked;

// ...

string[] files = GetFiles(directoryPath, searchPattern,

System.IO.SearchOption.AllDirectories);

files.AsParallel().ForAll( (filename) =>

{

Encrypt(filename);

WriteLine($" '{filename}' encrypted");

Increment(ref fileCount);

});

// ...Notice there’s no using System.Linq statement. Instead, there is the using static System.Linq.ParallelEnumerable directive, causing only extension methods from ParallelEnumerable to be in scope as extension methods. All the extension methods on classes like System.Linq.Enumerable will not be available as extension methods. For example, files.Select(…) will fail compilation because Select isn’t in scope on a string array (or even IEnumerable

In general, the best practice is to limit usage of the using static directive to a few classes that are used repeatedly throughout the scope (unlike Parallel) such as System.Console or System.Math. Similarly, when using static for enums, be sure the enum items are self-explanatory without their type identifier. For example, and perhaps my favorite, specify using Microsoft.VisualStudio.TestTools.UnitTesting.Assert in unit tests files to enable test assertion invocations such as IsTrue, AreEqual

The nameof Operator

Figure 3 includes another feature new in C# 6.0, the nameof operator. This is a new contextual keyword to identify a string literal that extracts a constant for (at compile time) the unqualified name of whatever identifier is specified as an argument. In Figure 3, nameof(filename) returns “filename,” the name of the Encrypt method’s parameter. However, nameof works with any programmatic identifier. For example, Figure 5 leverages nameof to pass the property name to INotifyPropertyChanged.PropertyChanged. (By the way, using the CallerMemberName attribute to retrieve a property name for the PropertyChanged invocation is still a valid approach for retrieving the property name.

Figure 5. Using the nameof Operator for INotifyPropertyChanged.PropertyChanged

public class Person : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

public event PropertyChangedEventHandler PropertyChanged;

public Person(string name)

{

Name = name;

}

private string _Name;

public string Name

{

get{ return _Name; }

set

{

if (_Name != value)

{

_Name = value;

PropertyChangedEventHandler propertyChanged = PropertyChanged;

if (propertyChanged != null)

{

propertyChanged(this,

new PropertyChangedEventArgs(nameof(Name)));

}

}

}

}

// ...

}

[TestClass]

public class PersonTests

{

[TestMethod]

public void PropertyName()

{

bool called = false;

Person person = new Person("Inigo Montoya");

person.PropertyChanged += (sender, eventArgs) =>

{

AreEqual(nameof(CSharp6.Person.Name), eventArgs.PropertyName);

called = true;

};

person.Name = "Princess Buttercup";

IsTrue(called);

}

}Notice that whether only the unqualified “Name” is provided (because it’s in scope) or the fully qualified CSharp6.Person.Name identifier is used as in the test, the result is only the final identifier (the last element in a dotted name).

By leveraging the nameof operator, it’s possible to eliminate the vast majority of “magic” strings that refer to code identifiers as long as they’re in scope. This not only eliminates runtime errors due to misspellings within the magic strings, which are never verified by the complier, but also enables refactoring tools like Rename to update all references to the name change identifier. And, if a name changes without a refactoring tool, the compiler will issue an error indicating that the identifier no longer exists.

String Interpolation

Figure 3 could be improved by not only specifying the exception message indicating the file wasn’t found, but also by displaying the file name itself. Prior to C# 6.0, you’d do this using string.Format in order to embed the filename into the string literal. However, composite formatting wasn’t the most readable. Formatting a person’s name, for example, required substituting placeholders based on the order of parameters as shown in the Figure 6 assignment of message.

Figure 6. Composite String Formatting Versus String Interpolation

[TestMethod]

public void InterpolateString()

{

Person person = new Person("Inigo", "Montoya") { Age = 42 };

string message =

string.Format("Hello! My name is {0} {1} and I am {2} years old.",

person.FirstName, person.LastName, person.Age);

AreEqual<string>

("Hello! My name is Inigo Montoya and I am 42 years old.", message);

string messageInterpolated =

$"Hello! My name is {person.FirstName} {person.LastName} and I am

{person.Age} years old.";

AreEqual<string>(message, messageInterpolated);

}Notice the alternate approach to composite formatting with the assignment to messageInterpolated. In this example, the expression assigned to messageInterpolated is a string literal prefixed with a “$” and curly brackets identify code that is embedded inline within the string. In this case, the properties of person are used to make this string significantly easier to read than a composite string. Furthermore, the string interpolation syntax reduces errors caused by arguments following the format string that are in improper order, or missing altogether and causing an exception. (In Visual Studio 2015 Preview there’s no $ character and, instead, each left curly bracket requires a slash before it. Releases following Visual Studio 2015 Preview are updated to use the $ in front of the string literal syntax instead.)

String interpolation is transformed at compile time to invoke an equivalent string.Format call. This leaves in place support for localization as before (though still with traditional format strings) and doesn’t introduce any post compile injection of code via strings.

Figure 7 shows two more examples of string interpolation.

Figure 7. Using String Interpolation in Place of string.Format

public Person(string firstName, string lastName, int? age=null)

{

Name = $"{firstName} {lastName}";

Age = age;

}

private static void Encrypt(string filename)

{

if (!System.IO.File.Exists(filename))

{

throw new ArgumentException(

$"The file, '{filename}', does not exist.", nameof(filename));

}

// ...

}Notice that in the second case, the throw statement, both string interpolation and the nameof operator are leveraged. String interpolation is what causes the ArgumentException message to include the file name (that is, “The file, ‘c:\data\missingfile.txt’ does not exist”). The use of the nameof operator is to identify the name of the Encrypt parameter (“filename”), the second argument of the ArgumentException constructor. Visual Studio 2015 is fully aware of the string interpolation syntax, providing both color coding and IntelliSense for the code blocks embedded within the interpolated string.

Null-Conditional Operator

Although eliminated in Figure 2 for clarity, virtually every Main method that accepts arguments requires checking the parameter for null prior to invoking the Length member to determine how many parameters were passed in. More generally, it’s a very common pattern to check for null before invoking a member in order to avoid a System.NullReferenceException (which almost always indicates an error in the programming logic). Because of the frequency of this pattern, C# 6.0 introduces the “?.” operator known as the null-conditional operator:

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

switch (args?.Length)

{

// ...

}

}The null-conditional operator translates to checking whether the operand is null prior to invoking the method or property (Length in this case). The logically equivalent explicit code would be (although in the C# 6.0 syntax the value of args is only evaluated once):

(args != null) ? (int?)args.Length : nullWhat makes the null-conditional operator especially convenient is that it can be chained. If, for example, you invoke string[] names = person?.Name?.Split(‘ ‘), Split will only be invoked if both person and person.Name are not null. When chained, if the first operand is null, the expression evaluation is short-circuited, and no further invocation within the expression call chain will occur. Beware, however, you don’t unintentionally neglect additional null-conditional operators. Consider, for example, names = person?.Name.Split(‘ ‘). If there’s a person instance but Name is null, a NullReferenceException will occur upon invocation of Split. This doesn’t mean you must use a chain of null-conditional operators, but rather that you should be intentional about the logic. In the Person case, for example, if Name is validated and can never be null, no additional null-conditional operator is necessary.

An important thing to note about the null-conditional operator is that, when utilized with a member that returns a value type, it always returns a nullable version of that type. For example, args?.Length returns an int?, not simply an int. Although perhaps a little peculiar (in comparison to other operator behavior), the return of a nullable value type occurs only at the end of the call chain. The result is that calling the dot (“.”) operator on Length only allows invocation of int (not int?) members. However, encapsulating args?.Length in parenthesis—forcing the int? result via parentheses operator precedence—will invoke the int? return and make the Nullable

The null-conditional operator is a great feature on its own. However, using it in combination with a delegate invocation resolves a C# pain point that has existed since C# 1.0. Note how in Figure 5 I assign the PropertyChange event handler to a local copy (propertyChanged) before checking the value for null and then finally firing the event. This is the easiest thread safe way to invoke events without risking that an event unsubscribe will occur between the time the check for null occurs and when the event is fired. Unfortunately, this is non-intuitive and I frequently encounter code that doesn’t follow this pattern—with the result of inconsistent NullReferenceExceptions. Fortunately, with the introduction of the null-conditional operator in C# 6.0, this issue is resolved.

With C# 6.0, the code snippet changes from:

PropertyChangedEventHandler propertyChanged = PropertyChanged;

if (propertyChanged != null)

{

propertyChanged(this, new PropertyChangedEventArgs(nameof(Name)));

}to simply:

PropertyChanged?.Invoke(propertyChanged(

this, new PropertyChangedEventArgs(nameof(Name)));And, because an event is just a delegate, the same pattern of invoking a delegate via the null-conditional operator and an Invoke is always possible. This feature, perhaps more than any other in C# 6.0, is sure to change the way you write C# code in the future. Once you leverage null-conditional operators on delegates, chances are you’ll never go back and code the old way (unless, of course, you’re stuck in a pre-C# 6.0 world.)

Null-conditional operators can also be used in combination with an index operator. For example, when you use them in combination with a Newtonsoft.JObject, you can traverse a JSON object to retrieve specific elements, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. A Console Color Configuration Example

string jsonText =

@"{

'ForegroundColor': {

'Error': 'Red',

'Warning': 'Red',

'Normal': 'Yellow',

'Verbose': 'White'

}

}";

JObject consoleColorConfiguration = JObject.Parse(jsonText);

string colorText = consoleColorConfiguration[

"ForegroundColor"]?["Normal"]?.Value<string>();

ConsoleColor color;

if (Enum.TryParse<ConsoleColor>(colorText, out color))

{

Console.ForegroundColor = colorText;

}It’s important to note that, unlike most collections within MSCORLIB, JObject doesn’t throw an exception if an index is invalid. If, for example, ForegroundColordoesn’t exist, JObject returns null rather than throwing an exception. This is significant because using the null-conditional operator on collections that throw an IndexOutOfRangeException is almost always unnecessary and may imply safety when no such safety exists. Returning to the snippet showing the Main and args example, consider the following:

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

string directoryPath = args?[0];

string searchPattern = args?[1];

// ...

}What makes this example dangerous is that the null-conditional operator gives a false sense of security, implying that if args isn’t null then the element must exist. Of course, this isn’t the case because the element may not exist even if args isn’t null. Because checking for the element count with args?.Length already verifies that args isn’t null, you never really need to also use the null-conditional operator when indexing the collection after checking length. In conclusion, avoid using the null-conditional operator in combination with the index operator if the index operator throws an IndexOutOfRangeException for non-existent indexes. Doing so leads to a false sense of code validity.

Default Constructors in Structs

Another C# 6.0 feature to be cognizant of is support for a default (parameterless) constructor on a value type. This was previously disallowed because the constructor wouldn’t be called when initializing arrays, defaulting a field of type struct, or initializing an instance with the default operator. In C# 6.0, however, default constructors are now allowed with the caveat that they’re only invoked when the value type is instantiated with the new operator. Both array initialization and explicit assignment of the default value (or the implicit initialization of a struct field type) will circumvent the default constructor.

To understand how the default constructor is leveraged, consider the example of the ConsoleConfiguration class shown in Figure 9. Given a constructor, and its invocation via the new operator as shown in the CreateUsingNewIsInitialized method, structs will be fully initialized. As you’d expect, and as is demonstrated in Figure 9, constructor chaining is fully supported, whereby one constructor can call another using the “this” keyword following the constructor declaration.

Figure 9. Declaring a Default Constructor on a Value Type

using Newtonsoft.Json.Linq;

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.IO;

public struct ConsoleConfiguration

{

public ConsoleConfiguration() :

this(ConsoleColor.Red, ConsoleColor.Yellow, ConsoleColor.White)

{

Initialize(this);

}

public ConsoleConfiguration(ConsoleColor foregroundColorError,

ConsoleColor foregroundColorInformation,

ConsoleColor foregroundColorVerbose)

{

// All auto-properties and fields must be set before

// accessing expression bodied members

ForegroundColorError = foregroundColorError;

ForegroundColorInformation = foregroundColorInformation;

ForegroundColorVerbose = foregroundColorVerbose;

}

private static void Initialize(ConsoleConfiguration configuration)

{

// Load configuration from App.json.config file ...

}

public ConsoleColor ForegroundColorVerbose { get; }

public ConsoleColor ForegroundColorInformation { get; }

public ConsoleColor ForegroundColorError { get; }

// ...

// Equality implementation excluded for elucidation

}

[TestClass]

public class ConsoleConfigurationTests

{

[TestMethod]

public void DefaultObjectIsNotInitialized()

{

ConsoleConfiguration configuration = default(ConsoleConfiguration);

AreEqual<ConsoleColor>(0, configuration.ForegroundColorError);

ConsoleConfiguration[] configurations = new ConsoleConfiguration[42];

foreach(ConsoleConfiguration item in configurations)

{

AreEqual<ConsoleColor>(default(ConsoleColor),

configuration.ForegroundColorError);

AreEqual<ConsoleColor>(default(ConsoleColor),

configuration.ForegroundColorInformation);

AreEqual<ConsoleColor>(default(ConsoleColor),

configuration.ForegroundColorVerbose);

}

}

[TestMethod]

public void CreateUsingNewIsInitialized()

{

ConsoleConfiguration configuration = new ConsoleConfiguration();

AreEqual<ConsoleColor>(ConsoleColor.Red,

configuration.ForegroundColorError);

AreEqual<ConsoleColor>(ConsoleColor.Yellow,

configuration.ForegroundColorInformation);

AreEqual<ConsoleColor>(ConsoleColor.White,

configuration.ForegroundColorVerbose);

}

}There’s one key point to remember about structs: all instance fields and auto-properties (because they have backing fields) must be fully initialized prior to invoking any other instance members. As a result, in the example in Figure 9, the constructor can’t call the Initialize method until all fields and auto-properties have been assigned. Fortunately, if a chained constructor handles all requisite initialization and is invoked via a “this” invocation, the compiler is clever enough to detect that it isn’t necessary to initialize data again from the body of the non-this invoked constructor, as shown in Figure 9.

Auto-Property Improvements

Notice also in Figure 9 that the three properties (for which there are no explicit fields) are all declared as auto-properties (with no body) and only a getter. These getter-only auto-properties are a C# 6.0 feature for declaring read-only properties that are backed (internally) by a read-only field. As such, these properties can only be modified from within the constructor.

Getter-only auto-properties are available in both structs and class declarations, but they’re especially important to structs because of the best practice guideline that structs be immutable. Rather than the six or so lines needed to declare a read-only property and initialize it prior to C# 6.0, now a single-line declaration and the assignment from within the constructor are all that’s needed. Thus, declaration of immutable structs is now not only the correct programming pattern for structs, but also the simpler pattern—a much appreciated change from prior syntax where coding correctly required more effort.

A second auto-property feature introduced in C# 6.0 is support for initializers. For example, I can add a static DefaultConfig auto-property with initializer to ConsoleConfiguration:

// Instance property initialization not allowed on structs.

static private Lazy<ConsoleConfiguration> DefaultConfig{ get; } =

new Lazy<ConsoleConfiguration>(() => new ConsoleConfiguration());Such a property would provide a single instance factory pattern for accessing a default ConsoleConfigurtion instance. Notice that rather than assigning the getter only auto-property from within the constructor, this example leverages System.Lazy

Note that auto-property initializers aren’t allowed on instance members of structs (although they’re certainly allowed on classes).

Expression Bodied Methods and Auto-Properties

Another feature introduced in C# 6.0 is expression bodied members. This feature exists for both properties and methods and allows the use of the arrow operator (=>) to assign an expression to either a property or method in place of a statement body. For example, because the DefaultConfig property in the previous example is both private and of type Lazy

static public ConsoleConfiguration GetDefault() => DefaultConfig.Value;However, in this snippet, notice there’s no statement block type method body. Rather, the method is implemented with only an expression (not a statement) prefixed with the lambda arrow operator. The intent is to provide a simple one-line implementation without all the ceremony, and one that’s functional with or without parameters in the method signature:

private static void LogExceptions(ReadOnlyCollection<Exception> innerExceptions) =>

LogExceptionsAsync(innerExceptions).Wait();In regard to properties, note that the expression bodies work only for read-only (getter-only) properties. In fact, the syntax is virtually identical to that of the expression bodied methods except that there are no parentheses following the identifier. Returning to the earlier Person example, I could implement read-only FirstName and LastName properties using expression bodies, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Expression Bodied Auto-Properties

public class Person

{

public Person(string name)

{

Name = name;

}

public Person(string firstName, string lastName)

{

Name = $"{firstName} {lastName}";

Age = age;

}

// Validation ommitted for elucidation

public string Name {get; set; }

public string FirstName => Name.Split(' ')[0];

public string LastName => Name.Split(' ')[1];

public override string ToString() => "{Name}({Age}";

}Furthermore, expression-bodied properties can also be used on index members, returning an item from an internal collection, for example.

Dictionary Initializer

Dictionary type collections are a great means for defining a name value pair. Unfortunately, the syntax for initialization is somewhat suboptimal:

{ {"First", "Value1"}, {"Second", "Value2"}, {"Third", "Value3"} }To improve this, C# 6.0 includes a new dictionary assignment type syntax:

Dictionary<string, ConsoleColor> colorMap =

new Dictionary<string, ConsoleColor>

{

["Error"] = ConsoleColor.Red,

["Information"] = ConsoleColor.Yellow,

["Verbose"] = ConsoleColor.White

};To improve the syntax, the language team introduced the assignment operator as a means of associating a pair of items that make a lookup (name) value pair or map. The lookup is whatever the index value (and data type) the dictionary is declared to be.

Exception Improvements

Not to be outdone, exceptions also had a couple of minor language tweaks in C# 6.0. First, it’s now possible to use await clauses within both catch and finally blocks, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Using Await Within Catch and Finally Blocks

public static async Task<int> EncryptFilesAsync(string directoryPath, string searchPattern = "*")

{

ConsoleColor color = Console.ForegroundColor;

try

{

// ...

}

catch (System.ComponentModel.Win32Exception exception)

if (exception.NativeErrorCode == 0x00042)

{

// ...

}

catch (AggregateException exception)

{

await LogExceptionsAsync(exception.InnerExceptions);

}

finally

{

Console.ForegroundColor = color;

await RemoveTemporaryFilesAsync();

}

}Since the introduction of await in C# 5.0, support for await in catch and finally blocks turned out to be far more sought after than originally expected. For example, the pattern of invoking asynchronous methods from within a catch or finally block is fairly common, especially when it comes to cleaning up or logging during those times. Now, in C# 6.0, it’s finally possible.

The second exception-related feature (which has been available in Visual Basic since 1.0) is support for exception filters such that on top of filtering by a particular exception type, it’s now possible to specify an if clause to further restrict whether the exception will be caught by the catch block or not. (On occasion this feature has also been leveraged for side effects such as logging exceptions as an exception “flies by” without actually performing any exception processing.) One caution to note about this feature is that, if there’s any chance your application might be localized, avoid catch conditional expressions that operate via exception messages because they’ll no longer work without changes following localization.

Wrapping Up

One final point to mention about all the C# 6.0 features is that although they obviously require the C# 6.0 compiler, included with Visual Studio 2015 or later, they do not require an updated version of the Microsoft .NET Framework. Therefore, you can use C# 6.0 features even if you’re compiling against the .NET Framework 4, for example. The reason this is possible is that all features are implemented in the compiler, and don’t have any .NET Framework dependencies.

With that whirlwind tour, I wrap up my look at C# 6.0. The only two remaining features not discussed are support for defining a custom Add extension method to help with collection initializers, and some minor but improved overload resolution. In summary, C# 6.0 doesn’t radically change your code, at least not in the way that generics or LINQ did. What it does do, however, is make the right coding patterns simpler. The null-conditional operator of a delegate is probably the best example of this, but so, too, are many of the other features including string interpolation, the nameof operator and auto-property improvements (especially for read-only properties).

For additional information here are a few additional references:

- Mark Michaelis’ C# Blog with 6.0 updates since writing this article: intellitect.com/EssentialCSharp/

- C# 6.0 language discussions: roslyn.codeplex.com/discussions

In addition, although not available until the second quarter of 2015, look for the next release of my book, “Essential C# 6.0” (intellitect.com/EssentialCSharp).

By the time you read this, C# 6.0 feature discussions will likely be closed. However, there’s little doubt that a new Microsoft is emerging, one that’s committed to investing in cross-platform development using open source best practices that allow the development community to share in creating great software. For this reason, you’ll soon be able to read about early design discussions on C# 7.0, because this time the discussion will take place in an open source forum.

Thanks to the following Microsoft technical expert for reviewing this article: Mads Torgersen.

This article was originally posted here in the January 2015 issue of MSDN Magazine.