When Microsoft announced .NET 5 at Microsoft Build 2019 in May, it marked an important step forward for developers working across desktop, Web, mobile, cloud and device platforms. In fact, .NET 5 is that rare platform update that unifies divergent frameworks, reduces code complexity and significantly advances cross-platform reach.

This is no small task. Microsoft is proposing to merge the source code streams of several key frameworks—.NET Framework, .NET Core and Xamarin/Mono. The effort will even unify threads that separated at inception at the turn of the century, and provide developers one target framework for their work.

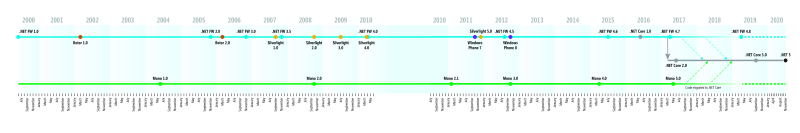

The source code flow concept in Figure 1 shows how the timeline for each framework syncs up, and ultimately merges into a single thread as .NET 5 in November 2020. (Note that .NET Framework has been shortened to .NET FW in the image.) When released, .NET 5 will eclipse .NET Framework 4.8, Mono 5.0, and .NET Core 3.0.

Figure 1 Source Code Flow Concept from .NET, Mono, and Shared Source Initiative to .NET 5

Admittedly, Figure 1 is more conceptual than reality, with source code forking (more likely just copying) rather than branching, and features (like Windows Presentation Foundation [WPF] or Windows Forms) migrating rather than merging. Still, the infographic provides a reasonably transparent view of the ancestral history of the .NET source code, showing its evolution from the three major branches all the way to .NET 5.

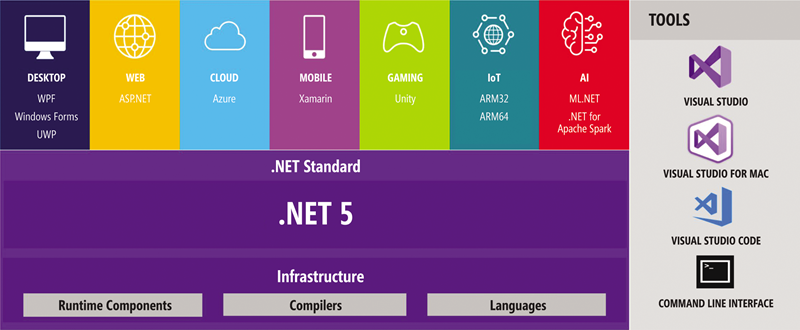

The result of this work is a unified platform with the .NET 5 framework executing on all platforms (desktop, Web, cloud, mobile and so on). Figure 2 depicts this unified architecture.

Figure 2 .NET 5—a Unified Platform

Origin Story

It’s fascinating how the different .NET frameworks—such as Microsoft’s Shared Source Common Initiative (Rotor), SilverLight, Windows Phone, .NET Core, and .NET Framework (but not Mono)—were originally compiled from the same source code. In other words, all the source code was maintained in a single repository and shared by all .NET frameworks. In so doing, Microsoft was able to ensure that APIs that were common to different frameworks would come from the same source code and have the same signatures. The only differences were which APIs were shared. (Note the use of .NET “framework,” lowercase, referring to all .NET frameworks in general, vs .NET “Framework,” uppercase, referring to the Windows .NET Framework, such as .NET Framework 4.8.)

To achieve a single source targeting different frameworks, various subsetting techniques, such as a multitude of #ifdefs, were used. Also of interest is how an orthogonal set of subsetting techniques (that is, different #ifdefs) were baked into the .NET source code to build Rotor’s cross-platform support, enabling rapid development of both Silverlight and (much later) .NET Core from the same code base.

While the orthogonal set of subsetting techniques remains, the one that enables cross-platform compilation—the subsetting to produce the different frameworks—is being removed. (See, for example, the pull request at bit.ly/2WdSzv2 that removes several #ifdefs that are stale.) The reason it’s possible to remove them today is because within days after the .NET 1.1 release, the .NET Core and .NET Framework source code was forked (more like copied). This in fact explains why there are two separate .NET source code Web sites: .NET Framework at referencesource.microsoft.com and .NET Core at source.dot.net. These are two separate code bases.

The decision to fork rather than continue the use of subsetting reflects the tension between maintaining backward compatibility (a high priority for the .NET Framework) and innovation (the priority of .NET Core). There were simply too many cases where maintaining compatibility conflicted with correcting or improving the .NET APIs, such that the source code had to be separated if both goals were to be achieved. Using #ifdefs was no longer a functional way to separate out the frameworks when, in fact, the APIs were different and version incompatible.

Over time, however, another conflict arose—that of allowing developers to create libraries that could successfully execute within both frameworks. To achieve this, an API standard was needed to assure developers that a framework would have a specific set of APIs identified by the standard. That way, if they leveraged only the APIs within the standard, their library would be cross-framework compatible (the exact same assembly could run on different frameworks—without even recompiling).

With each new feature added to .NET (for example Span

Come Together

The two frameworks began to look more and more alike because of the standard. As the APIs became more consistent, the obvious question began to arise: Why not move the separate code bases back together? And, in fact, starting with .NET Core 3.0 preview, so much of the .NET Framework WPF and Windows API was cherry-picked and merged into the .NET Core 3.0 code base, that this is exactly what happened. The source code for .NET Core 3.0 became one and the same with the modern day (desktop, cloud, mobile and IoT) functionality in .NET Framework 4.8.

At this point there’s still one major .NET framework that I haven’t covered: Mono/Xamarin. Although the source code for Rotor was publicly available, using it would’ve violated the license agreement. Instead, Mono began as a separate green field development effort with the vision to create a Linux-compatible version of .NET. The Mono framework continued to grow over time, until the company (Ximian) was acquired in 2003 by Novell and then shuttered eight years later following Novell’s sale to Attachmate. Ximian management quickly reformed in May 2011 as Xamarin. And less than two years later, Xamarin developed a cross-platform UI code base that ran on both Android and iOS, leveraging a now closed-source, cross-platform version of Mono under the covers.

In 2016 Microsoft acquired Xamarin to bring all the .NET framework source code under the control of a single company. Shortly after, Mono and the Xamarin SDK would be released as open source.

This brings us to where we are in the first half of 2019, with essentially two main code bases going forward: .NET Core 3.0 and Mono/Xamarain. (While Microsoft will support .NET Framework 4.8 on Windows for as long as anyone can forecast, .NET Core 3.0 and later .NET 5 will eclipse it as the strategic platform for new applications going forward.) Alongside this is the .NET Standard and the unification of APIs into the soon-to-be-released .NET Standard 2.1.

Again, the question arises, with APIs moving closer and closer, can we not merge .NET Core 3.0 with Mono? It’s an effort, in fact, that has already begun. Mono today is already one-third Mono source, one-third CoreFx, and one-third .NET Framework reference source. That set the stage for .NET 5 to be announced at Microsoft Build 2019.

The Advantages of .NET 5

This unified version of .NET 5 will support all .NET application types: Xamarin, ASP.NET, IoT and desktop. Furthermore, it will leverage a single CoreFX/Base Class Library (BCL), two separate runtimes and runtime code bases (because it’s really hard to single source two runtimes intended to be critically different), and a single tool chain (such as dotnet CLI). The result will be uniformity across behaviors, APIs and developer experiences. For example, rather than having three implementations of the System.* APIs, there will be a single set of libraries that run on each of the different platforms.

There are a host of advantages with the unification of .NET. Unifying the framework, runtimes, and developer toolsets into a single code base will result in a reduction in the amount of duplicate code that developers (both Microsoft and the community) will need to maintain and expand. Also, as we’ve come to expect from Microsoft these days, all the .NET 5 source code will be open source.

With the merger, many of the features exclusive to each individual framework will become available to all platforms. For example, csproj types for these platforms will be unified into the well-loved and simple .NET Core csproj file format. A .NET Framework project type, therefore, will be able to take advantage of the .NET Core csproj file format. While a conversion to .NET Core csproj file formats is necessary for Xamarin and .NET Framework (including WPF and Windows Forms) csproj files, the task is similar to the conversion from ASP.NET to ASP.NET Core. Fortunately, today it’s even easier to do thanks to tools like ConvertProjectToNETCore3 (see bit.ly/2W5Lk3D).

Another area of significant difference is in the runtime behavior of Xamarin and .NET Core/.NET Framework. The former uses a static compilation model, with ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation that compiles source code down to the native source code of the platform. By contrast, .NET Core and .NET Framework use just-in-time (JIT) compilation. Fortunately, with .NET 5, both models will be supported, depending on the project type target.

For example, you can choose to compile your .NET 5 project into a single executable that will use the JIT compiler (jitter) at runtime, or a native compiler to work on iOS or Android platforms. Most projects will leverage the jitter, but for iOS all the code is AOT. For client-side Blazor, the runtime is Web Assembly (WASM), and Microsoft intends to AOT compile a small amount of managed code (around 100kb to 300kb), while the rest will be interpreted. (AOT code is large, so the wire cost is quite a burden to pay.)

In .NET Core 3.0 you can compile to a single executable, but that executable is actually a compressed version of all the files needed to execute at runtime. When you execute the file, it first expands itself out into a temporary directory and then executes the entry point of the application from the directory that contains all the files. By contrast, .NET 5 will create a true, single-executable file that can execute directly in place.

Another remarkable feature of .NET 5 is interoperability with source code from Java and Objective-C (including Swift). This has been a feature of Xamarin since the early releases, but will extend to all .NET 5 projects. You’ll be able to include jar files in your csproj file, for example, and you’ll be able to call directly from your .NET code into Java or Objective-C code. (Unfortunately, support for Objective-C will likely come later than Java.) It should be noted that interoperability between .NET 5 and Java/Objective-C is only targeted at in-process communication. Distributed communication to other processes on the same machine or even processes on a different machine will likely require serialization into a REST- or RPC-based distributed invocation.

What’s Not in .NET 5

While there’s a significant set of APIs available in the .NET 5 framework, it doesn’t include everything that might have been developed over the last 20 or so years. It’s reasonable to expect that all the APIs identified in .NET Standard 2.1 will be supported, but some of the more “legacy” APIs, including Web Forms, Windows Communication Foundation (WCF) server and Windows Workflow, will not. These are destined to remain in .NET Framework only. If you wish to achieve the same functionality within .NET 5, consider porting these APIs as follows:

- ASP.NET Web Forms => ASP.NET Blazor

- WCF server and remoting => gRPC

- Windows Workflow (WF) => Core WF (github.com/UiPath/corewf)

The lack of WCF server support is no doubt disappointing to some. However, Microsoft recently decided to release the software under an MIT open source license, where its destiny is in control of the community (see github.com/CoreWCF/CoreWCF). There’s still a tremendous amount of work to be done to release independently of the .NET Framework, but in the meantime, the client-side WCF APIs are available (see github.com/dotnet/wcf).

A Declaration of Intent

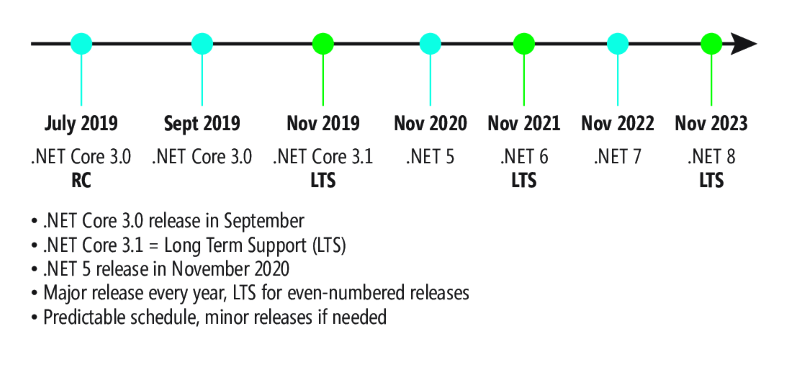

Even as Microsoft makes plans to unify its developer frameworks under .NET 5, the company has announced that it’s adopting a regular cadence for its unified .NET releases (see Figure 3). Going forward, you can expect general availability versions of .NET to be released in Q4 of each year. Of these releases, every second version will be a Long Term Support (LTS) release, which Microsoft will support for a minimum of three years or one year after a subsequent LTS release, whichever is longer. In other words, you’ll always have at least three years to upgrade your application to the next LTS release. See bit.ly/2Kfkkw0 for more information on the .NET Core support policy, and what can be reasonably expected to become the .NET 5 and beyond support policy.

Figure 3 .NET Release Schedule

At this point, .NET 5 is still just an announcement—a declaration of intent, if you like. There’s lots of work to be done. Even so, the announcement is remarkable. When .NET Core was first released, the goal was to provide a cross-platform .NET version that could highlight Azure (perhaps especially the Platform-as-a-Service [PaaS] portions of Azure and support for .NET on Linux and within Linux containers).

In the original concept, the idea that all of .NET Framework could be ported to .NET Core wasn’t considered realistic. Around the time of the .NET Core 2.0 release, that began to change. Microsoft realized that it needed to define a framework standard for all .NET framework versions, to enable code running on one framework to be portable to another.

This standard, of course, became known as the .NET Standard. Its purpose was to identify the API that a framework needed to support so that libraries targeting the standard could count on a specific set of APIs being available. As it turned out, defining the standard and then implementing it with Xamarin/Mono, .NET Core, and .NET Framework became a key component that made the .NET 5 unification strategy possible.

For example, once each framework has implemented code that supports the .NET Standard set of APIs, it seems logical to work toward combining the separate code bases into one (a refactoring of sorts). And, where behavior isn’t the same (JIT versus AOT compilation, for example), why not merge the code so that all platforms support both approaches and features? The effort isn’t trivial, but the result is a huge step forward in reducing complexity and maintenance, while at the same time unifying the features to all platforms.

Perhaps surprisingly, the very .NET Standard that made unification possible will likely make .NET Standard irrelevant. In fact, with the emergence of .NET 5, it’s doubtful there will be another version of .NET Standard—.NET 5 and each version after that will be the standard.

Wrapping Up

They say timing is everything, and that’s true of .NET 5. A virtually comprehensive re-write of the .NET Framework wasn’t even conceivable when .NET Core development started. At the time, Microsoft was responding to demand to significantly enhance the Azure hosting experience on Linux, in containers, and on PaaS. As such, the company was laser-focused on getting something out to meet the demands of customers and the Azure product team.

With .NET Core 2.0 the mission expanded to matching the functionality found in the .NET Framework. Again, the team was laser-focused on releasing something viable, rather than taking on too much. But things began to change with .NET Core 3.0 and the implementation of .NET Standard 2.1. The idea of having to go in and make changes to three distinct frameworks when a new feature or bug came up was an irritation and an expense. And, like any good developer, the idea soon emerged to refactor the code as much as possible into a single code base.

And so, .NET 5 was born. And along with it was born the idea of unifying all the features of each framework—whether it was simple csproj formats, adopting open source development models, enabling interoperability with Java and Objective-C (including Swift), or supporting JIT and AOT compilation. Just like that, the idea of a single, unified framework became an obvious next step, and one I expect everyone both inside and outside of Microsoft will celebrate.

Thanks to the following Microsoft technical expert for reviewing this article: Rich Lander.

This article was originally posted here in the July 2019 issue of MSDN Magazine.