Exploring the .NET Core Build System

Those of you who have been following .NET Core over the past few years (has it been that long?) know all too well that the “build system” has experienced a significant amount of flux, whether it be dropping built-in support for gulp or the demise of Project.json. For me as a columnist, these changes have been challenging as I didn’t want you, my dear readers, to spend too much time learning about features and details that ultimately were only going to be around for a few months. This is why, for example, all my .NET Core-related articles were built on Visual Studio .NET 4.6-based _._CSPROJ files that referenced NuGet packages from .NET Core rather than actually compiled .NET Core projects.

This month, I’m pleased to report, the project file for .NET Core projects has stabilized into (would you believe) an MSBuild file. However, it’s not the same MSBuild file from earlier Visual Studio generations, but rather an improved—simplified—MSBuild file. It’s a file that (without getting into religious wars about curly vs. angle brackets) includes all the features of Project.json but with the accompanying tool support of the traditional MSBuild file we’ve come to know (and perhaps love?) since Visual Studio 2005. In summary, the features include open source, cross-platform compatibility, a simplified and human-editable format and, finally, full modern .NET tool support including wildcard file referencing.

Tooling Support

To be clear, features such as wild cards were always supported in MSBuild, but now the Visual Studio tooling works with them, as well. In other words, the most important news about MSBuild is that it’s tightly integrated as the build system foundation for all the new .NET Tooling—DotNet.exe, Visual Studio 2017, Visual Studio Code and Visual Studio for Mac—and with support for both .NET Core 1.0 and .NET Core 1.1 runtimes.

The big advantage of the strong coupling between .NET Tooling and MSBuild is that any MSBuild file you create is compatible with all the .NET Tooling and can be built from any platform.

The .NET Tooling for MSBuild integration is coupled via the MSBuild API, not just a command-line process. For example, executing the .NET CLI command Dotnet.exe Build doesn’t internally spawn the msbuild.exe process. However, it does call the MSBuild API in process to execute the work (both the MSBuild.dll and Microsoft.Build. assemblies). Even so, the output—regardless of the tool—is similar across platforms because there’s a shared logging framework with which all the .NET Tools register.

*.CSPROJ/MSBuild File Structure

As I mentioned, the file format itself is simplified down to the bare minimum. It supports wildcards, project and NuGet package references, and multiple frameworks. Furthermore, the project-type GUIDs found in the Visual Studio-created project files of the past are gone.

Figure 1 shows a sample *.CSPROJ/MSBuild file.

Figure 1. A Basic Sample CSProj/MSBuild File

<Project>

<PropertyGroup>

<TargetFramework>netcoreapp1.0</TargetFramework>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<Compile Include="**\*.cs" />

<EmbeddedResource Include="**\*.resx" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<PackageReference Include="Microsoft.NETCore.App">

<Version>1.0.1</Version>

</PackageReference>

<PackageReference Include="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<Version>1.0.0-*</Version>

<PrivateAssets>All</PrivateAssets>

</PackageReference>

</ItemGroup>

<Import Project="$(MSBuildToolsPath)\Microsoft.CSharp.targets" />

</Project>Let’s review the structure and capabilities in detail:

Simplified Header: To begin, notice that the root element is simply a Project element. Gone is the need for even the namespace and version attributes:

ToolsVersion="15.0" xmlns="https://schemas.microsoft.com/developer/msbuild/2003"(Though, they’re still created in the release candidate version tooling.) Similarly, even the need for importing the common properties is merely optional:

<Import Project=

"$(MSBuildExtensionsPath)$(MSBuildToolsVersion)\Microsoft.Common.props" />Project References: From the project file, you can add entries to the item group elements:

- NuGet Packages:

<PackageReference Include="Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration">

<Version>1.1.0</Version>

</PackageReference>- Project References:

<ProjectReference Include="..\ClassLibrary\ClassLibrary.csproj" />- Assembly References:

<Reference Include="MSBuild">

<HintPath>...</HintPath>

</Reference>A direct assembly reference should be the exception as a NuGet reference is generally preferred.

Wildcard Includes: Compiled code files and resource files can all be included via wildcards.

<Compile Include="**\*.cs" />

<EmbeddedResource Include="**\*.resx" />

<Compile Remove="CodeTemplates\**" />

<EmbeddedResource Remove="CodeTemplates\**" />However, you can still select specific files to ignore using the remove attribute. (Note that support for wildcards is frequently referred to as globbing.)

Multi-Targeting: To identify which platform you’re targeting, along with the (optional) output type, you can use a property group with the TargetFramework elements:

<PropertyGroup>

<TargetFramework>netcoreapp1.0</TargetFramework>

<TargetFramework>netstandard1.3</TargetFramework>

</PropertyGroup>Given these entries, the output for each target will be built into the bin\Debug or bin\Release directory (depending on which configuration you specify). If there’s more than one target, the build execution will place the output into a folder corresponding to the target framework name.

No Project Type GUIDs: Note that it’s no longer necessary to include a project-type GUID that identifies the type of project.

Visual Studio 2017 Integration

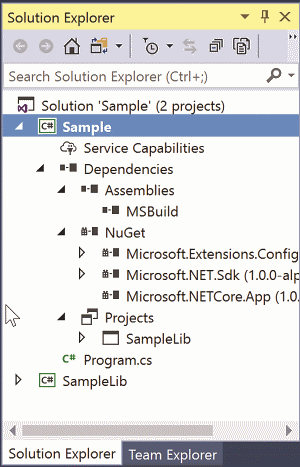

When it comes to Visual Studio 2017, Microsoft continues to provide a rich UI for editing the CSPROJ/MSBuild project file. Figure 2, for example, shows Visual Studio 2017 loaded with a CSPROJ file listing, slightly modified from Figure 1, that includes target framework elements for netcoreapp1.0 and net45, along with package references for Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration, Microsoft.NETCore.App, and Microsoft.NET.Sdk, plus an assembly reference to MSBuild, and a project reference to SampleLib.

Figure 2. Solution Explorer is a Rich UI on Top of a CSProj File

Notice how each dependency type—assembly, NuGet package or project reference—has a corresponding group node within the Dependencies tree in Solution Explorer.

Furthermore, Visual Studio 2017 supports dynamic reloading of the project and solution. For example, if a new file is added to the project directory—one that matches one of the globbing wild cards—Visual Studio 2017 automatically detects the changes and displays the files within the Solution Explorer. Similarly, if you exclude a file from a Visual Studio project (via the Visual Studio menu option or the Visual Studio properties window), Visual Studio will automatically update the project file accordingly. (For example, it will add a

Furthermore, edits to the project file will be automatically detected and reloaded into Visual Studio 2017. In fact, the Visual Studio project node within Solution Explorer now supports a built-in Edit

There’s built-in migration support within Visual Studio 2017 to convert projects to the new MSBuild format. If you accept its prompt, your project will automatically upgrade from a Project.json/.XPROJ type to an MSBUILD/.CSPROJ type. Note that such an upgrade will break backward compatibility with Visual Studio 2015 .NET Core projects, so you can’t have some of your team working on the same .NET Core project in Visual Studio 2017 while others use Visual Studio 2015.

MSBuild

I would be remiss to not point out that back in March 2016, Microsoft released MSBuild as open source on GitHub (github.com/Microsoft/msbuild) and contributed it to the .NET Foundation (dotnetfoundation.org). Establishing MSBuild as open source put it on track for platform portability to Mac and Linux—ultimately allowing it to become the underlying build engine for all the .NET Tooling.

Other than the CSPROJ\MSBuild file PackageReference element identified earlier, MSBuild version 15 doesn’t introduce many additional features beyond open source and cross platform. In fact, comparing the command-line help shows the options are identical. For those not already familiar with it, here’s a list of the most common options you should be familiar with from the general syntax MSBuild.exe [options] [project file]:

/target:

/property:

/maxcpucount[:n]: Specifies the number of CPUs to use. By default, msbuild runs on a single CPU (single-threaded). If synchronization isn’t a problem you can increase that by specifying the level of concurrency. If you specify the /maxcpucount option without providing a value, msbuild will use the number of processors on the computer.

/preprocess[:file]: Generates an aggregated project file by inlining all the included targets. This can be helpful for debugging when there’s a problem.

@file: Provides one (or more) response files that contains options. Such files have each command-line option on a separate line (comments prefixed with “#”). By default, MSBuild will import a file named msbuild.rsp from the first project or solution built. The response file is useful for identifying different build properties and targets depending on which environment (Dev, Test, Production) you’re building, for example.

Dotnet.exe

The dotnet.exe command line for .NET was introduced about a year ago as a cross-platform mechanism for generating, building and running .NET Core-based projects. As already mentioned, it has been updated so that it now relies heavily on MSBuild as the internal engine for the bulk of its work where this makes sense.

Here’s an overview of the various commands:

dotnet new: Creates your initial project. Out of the box this project generator supports the Console, Web, Lib, MSTest and XUnitTest project types. However, in the future you can expect it to allow you to provide custom templates so you can generate your own project types. (As it happens, the new command doesn’t rely on MSBuild for generating the project.)

dotnet restore: Reads through the project dependencies specified in the project file and downloads any missing NuGet packages and tools identified there. The project file itself can either be specified as an argument or be implied from the current directory (if there’s more than one project file in the current directory, specifying which one to use is required). Note that because restore leverages the MSBuild engine for its work, the dotnet command allows for additional MSBuild command-line options.

dotnet build: Calls on the MSBuild engine to execute the build target (by default) within the project file. Like the restore command, you can pass MSBuild arguments to the dotnet build command. For example, a command such as dotnet build /property:configuration=Release will trigger a Release build to be output rather than a Debug build (the default). Similarly, you can specify the MSBuild target using /target (or /t). The dotnet build /t:compile command, for example, will run the compile target.

dotnet clean: Removes all the build output so that a full build rather than an incremental build will execute.

dotnet migrate: Upgrades a Project.json/.XPROJ-based project into the .CSPROJ/MSBuild format.

dotnet publish: Combines all the build output along with any dependencies into a single folder, thereby staging it for deployment to another machine. This is especially useful for self-contained deployment that includes not only the compile output and the dependent packages, but even the .NET Core runtime itself. A self-contained application doesn’t have any prerequisites that a particular version of the .NET platform already be installed on the target machine.

dotnet run: Launches the .NET Runtime and hosts the project and/or the compiled assemblies to execute your program. Note that for ASP.NET, compilation isn’t necessary as the project itself can be hosted.

There’s a significant overlap between executing msbuild.exe and dotnet.exe, leaving you with the choice of which one to run. If you’re building the default msbuild target you can simply execute the command “msbuild.exe” from within the project directory and it will compile and output the target for you. The equivalent dotnet.exe command is “dotnet.exe msbuild.” On the other hand, if you’re running a “clean” target the command is “msbuild.exe /t:clean” with MSBuild, versus “dotnet.exe clean” with dotnet. Furthermore, both tools support extensions. MSBuild has a comprehensive extensibility framework both within the project file itself and via .NET assemblies (see bit.ly/2flUBza). Similarly, dotnet can be extended but the recommendation for this, too, essentially involves extending MSBuild plus a little more ceremony.

While I like the idea of dotnet.exe, in the end it doesn’t seem to offer much advantage over MSBuild except for doing the things that MSBuild doesn’t support (of which dotnet new and dotnet run are perhaps the most significant). In the end, I feel that MSBuild allows you to do the simple things easily while still enabling the complicated stuff when needed. Furthermore, even the complicated stuff in MSBuild can be simplified down by providing reasonable defaults. Ultimately, whether dotnet or MSBuild is preferable comes down to preference, and time will tell which the development community generally settles on for the CLI front end.

global.json

While Project.json functionality has migrated to CSPROJ, global.json is still fully supported. The file allows specification of project directories and package directories, and identifies the version of the SDK to use. Here’s a sample global.json file:

{

"projects": [ "src", "test" ],

"packages": "packages",

"sdk": {

"version": "1.0.0-preview3",

"runtime": "clr",

"architecture": "x64"

}

}The three sections correspond to the main purposes of the global.json file:

projects: Identifies the root directories in which .NET projects are located. The projects node is critical for debugging into the .NET Core source code. After cloning the source code, you can add the directory into the projects node and Visual Studio will then automatically load it up as a project within the solution.

packages: Indicates the location of your NuGet packages folder.

sdk: Specifies which version of the runtime to use.

Wrapping Up

In this article, I’ve provided a broad overview of all the places that MSBuild is leveraged within the .NET Tooling suite. Before closing, let me offer one bit of advice from my experience working on projects with thousands of lines of MSBuild. Don’t fall into the trap of scripting too much in a declarative, loosely typed language like the XML MSBuild schema. That’s not its purpose. Rather, the project files should be relatively thin wrappers that identify the order and dependencies among your build targets. If you let your MSBuild project file get too big, it can become a pain to maintain. Don’t wait too long before you refactor it into something like C# MSBuild tasks that can be debugged and easily unit tested.

Thanks to the following IntelliTect technical experts for reviewing this article: Kevin Bost.

This article was originally posted here in the January 2017 issue of MSDN Magazine.