Testing Early to Reduce the Cost of Bugs

Testing is a topic that has been written about in-depth. It is well understood that bugs in software are very costly. Cost can be measured in many ways, but the key metric we will look at in this blog is time (developer time, testing time, support time, etc.). Over the years, many people have attempted to quantify the exact time-cost of a bug. Though results can vary, it is cheaper to find and fix a bug earlier than later in the software development life cycle. In this post, we will look at various testing strategies, such as shifting left, to reduce the cost of bugs.

Shifting Left

At its most basic, shifting left simply means testing should be performed as early as possible in the software life cycle. When deficiencies are found early, the cost of fixing them is significantly lower. This idea is key. Whenever possible, shift left to move your tests earlier in the software life cycle.

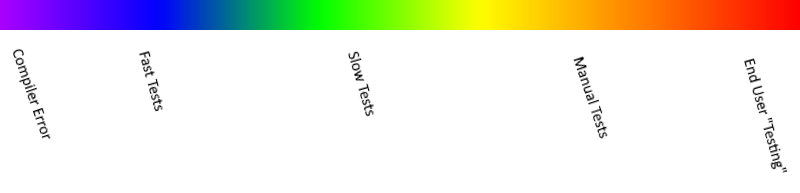

Rather than dictating firm rules, this guide aims to explain the “why” behind various testing strategies and provide guidance on when each should be used. For our purposes, it is helpful to think of different testing strategies as existing Io a spectrum rather than existing as fixed buckets. Often testing can be less than ideal and some flexibility of the boundaries is necessary.

The Software Life Cycle

For our purposes, we will assume that the software life cycle begins the moment a developer starts typing. Truthfully, the life cycle typically starts earlier with some form of design, but we will shift our focus to when the software is ready to be written and delivered. For the types of testing being discussed here, this is the furthest left that a test can be shifted.

Left Side of the Spectrum

On the left side of the spectrum, as soon as the developer starts typing, they are greeted with a wide host of information. IntelliSense tries to autocomplete keywords and identifiers. Similar to a scrupulous know-it-all code-reviewer who must be right, linters, and compilers point out flaws and typos in the words that the developer has written. At this point making changes to the code is easy, quick, and very fresh in the developer’s mind.

When possible, developers should strive to find issues at this stage. Therefore, this means spending time evaluating tools that can improve code quality and catch errors. This was one of the key motivators in the C# nullable reference types. Null reference exceptions are one of the most common errors, and this feature helps identify places where null reference exceptions may occur when compiling. In C#, we can even write our own custom code analysis (called Analyzers).

If it is possible to shift your testing this far left, do it. It is well worth the investment.

Right Side of the Spectrum

On the opposite side of the spectrum, developers have end-user testing. I use the term “testing” very loosely here. Most end users do not consider themselves testers; however, by monitoring your application’s health, you can often gain valuable insight into deficiencies. The major drawback to this approach is that finding issues at this stage is expensive and can ruin user perceptions of your software.

As much as possible, developers should be striving to stop bugs from ever reaching this stage.

Middle of the Spectrum

Finally, the area that many developers would see as “traditional” testing lies in the middle of the spectrum. These tests often take on several names: unit tests, integration tests, functional tests, UI tests, manual tests, or smoke tests.

All of these testing strategies have pros and cons. There are many metrics that can be used to measure the cost of tests. For our purposes, let’s think about the tests in terms of the time they take to run. On the left side of the spectrum, (fast tests) should be expected to have a very low time-cost to run. Moving further right on the spectrum causes the test speed to decrease and the cost to run to increase.

Which Testing Strategy?

With so many different choices it can often be confusing when deciding what types of tests to write. When making these decisions there are three key questions to consider.

What Are You Testing?

This may seem obvious, but typically when testing problems arise, they start with a misunderstanding of what is being tested. Is it a new class or method? Is it an integration between two components? Consider the changes and identify the use cases you want to test.

What Type of Failure Are You Trying to Prevent?

With fast tests, you are typically trying to catch programmer mistakes. The test serves as the first consumer of the code to verify that the code being tested meets expectations. With slower tests, you are typically trying to verify that various components (both inside and outside your software) work together. Consider what types of failures you are attempting to catch with the test.

How Far Left Can This Test be Reasonably Shifted?

Since it is important to reduce the cost of running tests, you want to shift the testing strategy as far left as possible. Often, to properly test some piece of functionality, it takes a combination of various testing strategies to ensure that everything is working correctly.

Testing In Practice

So, what does this look like in practice? In many projects, it translates to breaking down single larger, slow tests into multiple smaller, fast tests. This does not mean that slow tests should not be used. Rather, they should only be used to test cases that cannot be reasonably tested with a faster test.

Also, there is a hidden cost with slower tests. Slow tests tend to be larger and more difficult to diagnose when they fail. This can consume additional development time to diagnose and maintain when there are test failures. Shifting these tests left, possibly into multiple fast tests, can help eliminate these issues while still ensuring quality software.

Is There a Catch-All Testing Method?

In the end, there is no one right answer for testing. Like anything of value, the answer is “it depends.” This is why it is helpful to think of the various testing strategies as a spectrum, rather than a rigid set of rules. The next time you are getting ready to implement a feature or fix a bug, try verbalizing the answers to those questions and see if it helps improve the tests that you write.

Want More?

Feel free to leave any questions or comments below and check Mike Curn’s blog, Painless Bug Testing through the Isolation of Variables for more testing strategies.

Does Your Organization Need a Custom Solution?

Let’s chat about how we can help you achieve excellence on your next project!

Comments are closed.