Yield Return Statements

In my last column, I delved into the details of how the C# foreach statement works under the covers, explaining how the C# compiler implements the foreach capabilities in Common Intermediate Language (CIL). I also briefly touched on the yield keyword with an example (see Figure 1), but little to no explanation.

Figure 1. Yielding Some C# Keywords Sequentially

using System.Collections.Generic;

public class CSharpBuiltInTypes: IEnumerable<string>

{

public IEnumerator<string> GetEnumerator()

{

yield return "object";

yield return "byte";

yield return "uint";

yield return "ulong";

yield return "float";

yield return "char";

yield return "bool";

yield return "ushort";

yield return "decimal";

yield return "int";

yield return "sbyte";

yield return "short";

yield return "long";

yield return "void";

yield return "double";

yield return "string";

}

// The IEnumerable.GetEnumerator method is also required

// because IEnumerable<T> derives from IEnumerable.

System.Collections.IEnumerator

System.Collections.IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

// Invoke IEnumerator<string> GetEnumerator() above.

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

public class Program

{

static void Main()

{

var keywords = new CSharpBuiltInTypes();

foreach (string keyword in keywords)

{

Console.WriteLine(keyword);

}

}

}This is a continuation of that article, in which I provide more detail about the yield keyword and how to use it.

Iterators and State

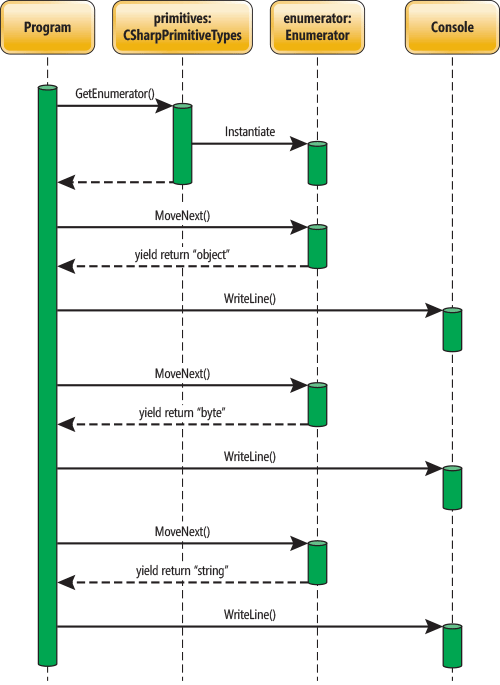

By placing a break point at the start of the GetEnumerator method in Figure 1, you’ll observe that GetEnumerator is called at the start of the foreach statement. At that point, an iterator object is created and its state is initialized to a special “start” state that represents the fact that no code has executed in the iterator and, therefore, no values have been yielded yet. From then on, the iterator maintains its state (location), as long as the foreach statement at the call site continues to execute. Every time the loop requests the next value, control enters the iterator and continues where it left off the previous time around the loop; the state information stored in the iterator object is used to determine where control must resume. When the foreach statement at the call site terminates, the iterator’s state is no longer saved. Figure 2 shows a high-level sequence diagram of what takes place. Remember that the MoveNext method appears on the IEnumerator

In Figure 2, the foreach statement at the call site initiates a call to GetEnumerator on the CSharpBuiltInTypes instance called keywords. As you can see, it’s always safe to call GetEnumerator again; “fresh” enumerator objects will be created when necessary. Given the iterator instance (referenced by iterator), foreach begins each iteration with a call to MoveNext. Within the iterator, you yield a value back to the foreach statement at the call site. After the yield return statement, the GetEnumerator method seemingly pauses until the next MoveNext request. Back at the loop body, the foreach statement displays the yielded value on the screen. It then loops back around and calls MoveNext on the iterator again. Notice that the second time, control picks up at the second yield return statement. Once again, the foreach displays on the screen what CSharpBuiltInTypes yielded and starts the loop again. This process continues until there are no more yield return statements within the iterator. At that point, the foreach loop at the call site terminates because MoveNext returns false.

Figure 2. Sequence Diagram with Yield Return

Another Iterator Example

Consider a similar example with the BinaryTree

In Figure 3, the iteration over the Pair

Figure 3. Using Yield to Implement BinaryTree

public struct Pair<T>: IPair<T>,

IEnumerable<T>

{

public Pair(T first, T second) : this()

{

First = first;

Second = second;

}

public T First { get; } // C# 6.0 Getter-only Autoproperty

public T Second { get; } // C# 6.0 Getter-only Autoproperty

#region IEnumerable<T>

public IEnumerator<T> GetEnumerator()

{

yield return First;

yield return Second;

}

#endregion IEnumerable<T>

#region IEnumerable Members

System.Collections.IEnumerator

System.Collections.IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

#endregion

}Implementing IEnumerable with IEnumerable

System.Collections.Generic.IEnumerable

The following code uses the Pair

var fullname = new Pair<string>("Inigo", "Montoya");

foreach (string name in fullname)

{

Console.WriteLine(name);

}Placing a Yield Return Within a Loop

It’s not necessary to hardcode each yield return statement, as I did in both CSharpPrimitiveTypes and Pair

Figure 4. Placing Yield Return Statements Within a Loop

public class BinaryTree<T>: IEnumerable<T>

{

// ...

#region IEnumerable<T>

public IEnumerator<T> GetEnumerator()

{

// Return the item at this node.

yield return Value;

// Iterate through each of the elements in the pair.

foreach (BinaryTree<T> tree in SubItems)

{

if (tree != null)

{

// Because each element in the pair is a tree,

// traverse the tree and yield each element.

foreach (T item in tree)

{

yield return item;

}

}

}

}

#endregion IEnumerable<T>

#region IEnumerable Members

System.Collections.IEnumerator

System.Collections.IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

#endregion

}In Figure 4, the first iteration returns the root element within the binary tree. During the second iteration, you traverse the pair of subelements. If the subelement pair contains a non-null value, you traverse into that child node and yield its elements. Note that foreach (T item in tree) is a recursive call to a child node.

As observed with CSharpBuiltInTypes and Pair

Figure 5. Using foreach with BinaryTree

// JFK

var jfkFamilyTree = new BinaryTree<string>(

"John Fitzgerald Kennedy");

jfkFamilyTree.SubItems = new Pair<BinaryTree<string>>(

new BinaryTree<string>("Joseph Patrick Kennedy"),

new BinaryTree<string>("Rose Elizabeth Fitzgerald"));

// Grandparents (Father's side)

jfkFamilyTree.SubItems.First.SubItems =

new Pair<BinaryTree<string>>(

new BinaryTree<string>("Patrick Joseph Kennedy"),

new BinaryTree<string>("Mary Augusta Hickey"));

// Grandparents (Mother's side)

jfkFamilyTree.SubItems.Second.SubItems =

new Pair<BinaryTree<string>>(

new BinaryTree<string>("John Francis Fitzgerald"),

new BinaryTree<string>("Mary Josephine Hannon"));

foreach (string name in jfkFamilyTree)

{

Console.WriteLine(name);

}And here are the results:

John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Joseph Patrick Kennedy

Patrick Joseph Kennedy

Mary Augusta Hickey

Rose Elizabeth Fitzgerald

John Francis Fitzgerald

Mary Josephine HannonThe Origin of Iterators

In 1972, Barbara Liskov and a team of scientists at MIT began researching programming methodologies, focusing on user-defined data abstractions. To prove much of their work, they created a language called CLU that had a concept called “clusters” (CLU being the first three letters of this term). Clusters were predecessors to the primary data abstraction that programmers use today: objects. During their research, the team realized that although they were able to use the CLU language to abstract some data representation away from end users of their types, they consistently found themselves having to reveal the inner structure of their data to allow others to intelligently consume it. The result of their consternation was the creation of a language construct called an iterator. (The CLU language offered many insights into what would eventually be popularized as “object-oriented programming.”)

Canceling Further Iteration: Yield Break

Sometimes you might want to cancel further iteration. You can do so by including an if statement so that no further statements within the code are executed. However, you can also use yield break to cause MoveNext to return false and control to return immediately to the caller and end the loop. Here’s an example of such a method:

public System.Collections.Generic.IEnumerable<T>

GetNotNullEnumerator()

{

if((First == null) || (Second == null))

{

yield break;

}

yield return Second;

yield return First;

}This method cancels the iteration if either of the elements in the Pair

A yield break statement is similar to placing a return statement at the top of a function when it’s determined there’s no work to do. It’s a way to exit from further iterations without surrounding all remaining code with an if block. As such, it allows multiple exits. Use it with caution, because a casual reading of the code might overlook the early exit.

How Iterators Work

When the C# compiler encounters an iterator, it expands the code into the appropriate CIL for the corresponding enumerator design pattern. In the generated code, the C# compiler first creates a nested private class to implement the IEnumerator

Figure 6. C# Equivalent of Compiler-Generated C# Code for Iterators

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

public class Pair<T> : IPair<T>, IEnumerable<T>

{

// ...

// The iterator is expanded into the following

// code by the compiler.

public virtual IEnumerator<T> GetEnumerator()

{

__ListEnumerator result = new __ListEnumerator(0);

result._Pair = this;

return result;

}

public virtual System.Collections.IEnumerator

System.Collections.IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return new GetEnumerator();

}

private sealed class __ListEnumerator<T> : IEnumerator<T>

{

public __ListEnumerator(int itemCount)

{

_ItemCount = itemCount;

}

Pair<T> _Pair;

T _Current;

int _ItemCount;

public object Current

{

get

{

return _Current;

}

}

public bool MoveNext()

{

switch (_ItemCount)

{

case 0:

_Current = _Pair.First;

_ItemCount++;

return true;

case 1:

_Current = _Pair.Second;

_ItemCount++;

return true;

default:

return false;

}

}

}

}Because the compiler takes the yield return statement and generates classes that correspond to what you probably would’ve written manually, iterators in C# exhibit the same performance characteristics as classes that implement the enumerator design pattern manually. Although there’s no performance improvement, the gains in programmer productivity are significant.

Creating Multiple Iterators in a Single Class

Previous iterator examples implemented IEnumerable

Figure 7. Using Yield Return in a Method That Returns IEnumerable

public struct Pair<T>: IEnumerable<T>

{

...

public IEnumerable<T> GetReverseEnumerator()

{

yield return Second;

yield return First;

}

...

}

public void Main()

{

var game = new Pair<string>("Redskins", "Eagles");

foreach (string name in game.GetReverseEnumerator())

{

Console.WriteLine(name);

}

}Note that you return IEnumerable

Yield Statement Requirements

You can use the yield return statement only in members that return an IEnumerator

The following additional restrictions on the yield statement result in compiler errors if they’re violated:

- The yield statement may appear only inside a method, a user-defined operator, or the get accessor of an indexer or property. The member must not take any ref or out parameter.

- The yield statement may not appear anywhere inside an anonymous method or lambda expression.

- The yield statement may not appear inside the catch and finally clauses of the try statement. Furthermore, a yield statement may appear in a try block only if there is no catch block.

Wrapping Up

Overwhelmingly, generics was the cool feature launched in C# 2.0, but it wasn’t the only collection-related feature introduced at the time. Another significant addition was the iterator. As I outlined in this article, iterators involve a contextual keyword, yield, that C# uses to generate underlying CIL code that implements the iterator pattern used by the foreach loop. Furthermore, I detailed the yield syntax, explaining how it fulfills the GetEnumerator implementation of IEnumerable

Much of this column derives from my “Essential C#” book (IntelliTect.com/EssentialCSharp), which I am currently in the midst of updating to “Essential C# 7.0.” For more information on this topic, check out Chapter 16.

Thanks to the following IntelliTect technical experts for reviewing this article: Kevin Bost.

This article was originally posted here in the June 2017 issue of MSDN Magazine.