Legacy Version of C# Multithreading

Multithreading patterns are used to address the multithreading complexities of monitoring an asynchronous operation, thread pooling, avoiding deadlocks, and implementing atomicity and synchronization across operations and data access.

This is a thorough blog that combs through all you’d need to know about multithreading if you were working in a legacy version of C#. Although lengthy, it wasn’t split into multiple blogs since several of the listings are referred to throughout.

Want to focus on a specific topic? Click below.

- Asynchronous Programming Model (APM)

- APM Signatures

- Passing State between APM Methods

- Beginner Topic – Synchronizing Console Using Lock

- Advanced Topic – Asynchronous Delegate Invocation in Detail

- The Event-Based Asynchronous Pattern

- Background Worker Pattern

- Dispatching to the Windows UI

In the ten years prior to the introduction of .NET 4.5 and C# 5.0, there were six versions of the .NET Framework and four versions of the C# language, and a similar number of corresponding multithreading patterns emerged. During that time, however, there were numerous improvements in multithreading and—as is frequently the case with frameworks and even languages—some patterns from those earlier versions were suboptimal. Suboptimal or not, as a C# developer you are likely to encounter these patterns either because you are developing for a .NET/C# version prior to .NET 4.5/C# 5.0 or because you are using an API from another framework that exposes one of the earlier patterns.

Discussing the Patterns

If you are lucky enough to be working solely with C# 5.0 or better, consider this blog an Advanced Topic, reading it simply to gain familiarity with the details of multithreading in the past. Alternatively, if you are still programming without the Task Programming Library (TPL) and the Task-based Asynchronous Pattern (TAP) and its async/await keywords, treat the remaining topics as an important part of the multithreading API available to you. Perhaps most importantly, this content describes how to effectively interact with the earlier patterns using the TPL and C# 5.0 and above.

Throughout these examples, exception handling has been eliminated for the purposes of elucidation.

Asynchronous Programming Model

One particularly prominent pattern established prior to the TPL is the Asynchronous Programming Model (APM) pattern. Given a long-running synchronous method X(), the APM pattern uses a BeginX() method to start X() equivalent work asynchronously and an EndX() method to conclude it. (Henceforth we will name these methods X, BeginX, and EndX.)

Using the APM Pattern

Listing 1 demonstrates the pattern by using the System.Net.WebRequest class to download a web page. We’ll assume for this example that the TPL and TAP are not available, and instead use the APM pattern. To maintain backward compatibility prior to TPL-related asynchronous methods being added, WebRequest also supports the APM pattern with the methods BeginGetResponse() (BeginX) and EndGetResponse() (EndX)—that is, asynchronous versions of the synchronous GetResponse() (X) method.

Listing 1: Using the APM Pattern with WebRequest

using System;

using System.IO;

using System.Net;

using System.Linq;

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

string url = "https://www.IntelliTect.com";

if (args.Length > 0)

{

url = args[0];

}

Console.Write(url);

WebRequest webRequest =

WebRequest.Create(url);

IAsyncResult asyncResult =

webRequest.BeginGetResponse(null, null);

// Indicate busy using dots; ideally (at least in a non-Console

// implementation) should use a callback rather than a wait.

while (

!asyncResult.AsyncWaitHandle.WaitOne(100))

{

Console.Write('.');

}

// Retrieve the results when finished downloading.

WebResponse response =

webRequest.EndGetResponse(asyncResult);

using (StreamReader reader =

new StreamReader(response.GetResponseStream()))

{

// Note: ReadToEnd() is blocking. A production implementation

//should offload this to another thread.

int length = reader.ReadToEnd().Length;

Console.WriteLine(FormatBytes(length));

}

}

static public string FormatBytes(long bytes)

{

string[] magnitudes =

new string[] { "GB", "MB", "KB", "Bytes" };

long max =

(long)Math.Pow(1024, magnitudes.Length);

return string.Format("{1:##.##} {0}",

magnitudes.FirstOrDefault(

magnitude =>

bytes > (max /= 1024) )?? "0 Bytes",

(decimal)bytes / (decimal)max).Trim();

}

}The results of Listing 1 appear in Output 1.

Output 1

https://www.IntelliTect.com..........29.36 KBAs mentioned, the key aspect of the APM pattern is the pair of BeginX and EndX methods with well-established signatures. The BeginX method returns a System.IAsyncResult object providing access to the state of the asynchronous call so it knows whether to wait or poll for completion. The EndX method then takes this return as an input parameter. This pairs up the two methods so that it is clear which BeginX method call pairs with which EndX method call. The APM pattern requires that for all BeginX invocations, there must be exactly one EndX invocation; thus multiple calls to EndX for the same IAsyncResult instance should not occur.

In Listing 1, we also use the IAsyncResult’s WaitHandle to determine when the asynchronous method completes. As we iteratively poll the WaitHandle, we print out periods to the console indicating that the download is running. Following that, we call EndGetResponse().

The EndX method serves four purposes. First, calling EndX will block further execution until the work requested completes successfully (or an error occurs and throws an exception). Second, if method X returns data, this data is accessible from the EndX method call. Third, if an exception occurs while performing the requested work, the exception will be re-thrown on the call to EndX, ensuring that the exception is visible to the calling code as though it had occurred on a synchronous invocation. Finally, if any resource needs cleanup due to X’s invocation, EndX will be responsible for cleaning up these resources.

APM Signatures

Together, the combination of the BeginX and EndX APM methods should match the synchronous version of the signature. Therefore, the return parameter on EndX should match the return parameters on the X method (GetResponse() in this case). Furthermore, the input parameters on the BeginX method also need to match. In the case of WebRequest.GetResponse() there are no parameters, but let’s consider a fictitious synchronous method:

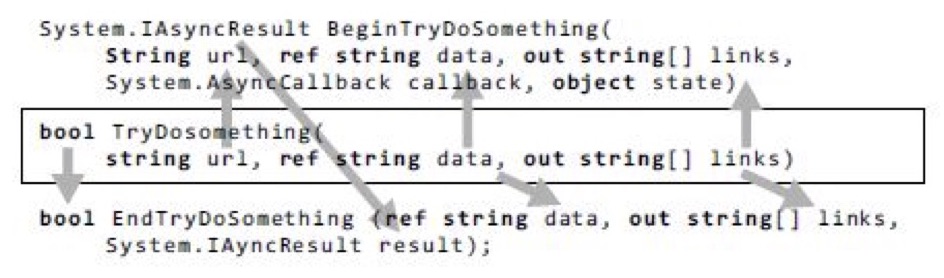

bool TryDoSomething(string url, ref string data, out string[] links)The parameters map from the synchronous method to the APM methods, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. APM Parameter Distribution

All input parameters map to the BeginX method. Similarly, the return parameter maps to the EndX return parameter. Also, notice that since the ref and out parameters return results, they are included in the EndX method signature. In contrast, url is just an input parameter, so it is not included in the EndX method.

Continuation Passing Style with AsyncCallback

There are two additional parameters on the BeginX method that were not included in the synchronous method: the callback parameter (a System.AsyncCallback delegate to be called when the method completes) and a state parameter of type object. Listing 2 demonstrates how they are used. (The output is the same as Output 1.)

Listing 2: Invoking an APM Method with Callback and State

using System;

using System.IO;

using System.Net;

using System.Linq;

using System.Threading;

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

string url = "https://www.intelliTechture.com";

if (args.Length > 0)

{

url = args[0];

}

Console.Write(url);

WebRequest webRequest = WebRequest.Create(url);

WebRequestState state =

new WebRequestState(webRequest);

IAsyncResult asyncResult =

webRequest.BeginGetResponse(

GetResponseAsyncCompleted, state);

// Indicate busy using dots.

while (

!asyncResult.AsyncWaitHandle.WaitOne(100))

{

Console.Write('.');

}

state.ResetEvent.Wait();

}

// Retrieve the results when finished downloading.

private static void GetResponseAsyncCompleted(

IAsyncResult asyncResult)

{

WebRequestState completedState =

(WebRequestState)asyncResult.AsyncState;

HttpWebResponse response =

(HttpWebResponse)completedState.WebRequest

.EndGetResponse(asyncResult);

Stream stream = response.GetResponseStream();

StreamReader reader = new StreamReader(stream);

// Note: ReadToEnd() is blocking. A production implementation

//should offload this to another thread.

int length = reader.ReadToEnd().Length;

Console.WriteLine(FormatBytes(length));

completedState.ResetEvent.Set();

completedState.Dispose();

}

// ...

}

class WebRequestState : IDisposable

{

public WebRequestState(WebRequest webRequest)

{

WebRequest = webRequest;

}

public WebRequest WebRequest { get; private set; }

private ManualResetEventSlim _ResetEvent =

new ManualResetEventSlim();

public ManualResetEventSlim ResetEvent

{ get { return _ResetEvent; } }

public void Dispose()

{

ResetEvent.Dispose();

GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

}

}In Listing 2, we pass data for both of the parameters on BeginGetResponse(). The first parameter is a delegate of type System.AsyncCallback that takes a single parameter of type System.AsyncResult. The AsyncCallback identifies the code that will execute once the asynchronous call completes. Registering a callback enables a fire-and-forget calling pattern called continuation passing style (CPS), rather than placing the EndGetResponse() and Console.WriteLine() code sequentially below BeginGetResponse(). With CPS, we can “register” the code that will execute upon completion of the asynchronous method. Note that it is still necessary to call EndGetResponse(), but by placing it in the callback we ensure that it doesn’t block the main thread while the asynchronous call completes.

Passing State between APM Methods

The state parameter is used to pass additional data to the callback when it executes. Listing 2 includes a WebRequestState class for passing additional data into the callback, and it includes the WebRequest itself in this case so that we can use it to call EndGetResponse(). One alternative to the WebRequestState class itself would be to use an anonymous method (including a lambda expression) with closures for the additional data, as shown in Listing 3.

Listing 3: Passing State Using Closure on an Anonymous Method

using System;

using System.IO;

using System.Net;

using System.Linq;

using System.Threading;

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

string url = "https://www.intelliTechture.com";

if (args.Length > 0)

{

url = args[0];

}

Console.Write(url);

WebRequest webRequest = WebRequest.Create(url);

ManualResetEventSlim resetEvent =

new ManualResetEventSlim();

IAsyncResult asyncResult =

webRequest.BeginGetResponse(

(completedAsyncResult) =>

{

HttpWebResponse response =

(HttpWebResponse)webRequest.EndGetResponse(

completedAsyncResult);

Stream stream =

response.GetResponseStream();

StreamReader reader =

new StreamReader(stream);

int length = reader.ReadToEnd().Length;

Console.WriteLine(FormatBytes(length));

resetEvent.Set();

resetEvent.Dispose();

},

null);

// Indicate busy using dots.

while (

!asyncResult.AsyncWaitHandle.WaitOne(100))

{

Console.Write('.');

}

resetEvent.Wait();

}

// ...

}Regardless of whether we pass the state via closures, notice that we are using a ManualResetEvent to signal when the AsyncCallback has completed. This is somewhat peculiar because IAsyncResult already includes a WaitHandle. The difference, however, is that IAsyncResult’s WaitHandle is set when the asynchronous method completes but before AsyncCallback executes. If we blocked on only IAsyncResult’s WaitHandle, we would be likely to exit the program before AsyncCallback has executed. For this reason, we use a separate ManualResetEvent.

Resource Cleanup

Another important APM rule is that no resource leaks should occur, even if the EndX method is mistakenly not called. Since WebRequestState owns the ManualResetEvent, it specifically owns a resource that requires such cleanup. To handle this task, the state object uses the standard IDisposable pattern with the IDispose() method.IDispose() method.

Calling APM Methods Using the TPL

Even though the TPL greatly simplifies making an asynchronous call on a long-running method, it is generally better to use the API-provided APM methods than to code the TPL against the synchronous version. The reason for this is that the API developer best understands what is the most efficient threading code to write, which data to synchronize, and which type of synchronization to use. Fortunately, there are special methods on the TPL’s TaskFactory that are designed specifically for invoking the APM methods. As a result, if you have access to the TPL but are using APM-related APIs, you can still use the TPL to invoke them.

APM with the TPL and CPS

The TPL includes a set of overloads on FromAsync for invoking APM methods. Listing 4 provides an example. The same listing expands on the other APM examples to support downloading of multiple URLs; see Output 2.

Listing 4: Using the TPL to Call the APM

using System;

using System.IO;

using System.Net;

using System.Linq;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

public class Program

{

static private object ConsoleSyncObject =

new object();

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

string[] urls = args;

if (args.Length == 0)

{

urls = new string[]

{

"https://www.habitat-spokane.org",

"https://www.partnersintl.org",

"https://www.iassist.org",

"https://www.fh.org",

"https://www.worldvision.org"

};

}

Task[] tasks = new Task[urls.Length];

for (int line = 0; line < urls.Length; line++)

{

tasks[line] = DisplayPageSizeAsync(

urls[line], line);

}

while (!Task.WaitAll(tasks, 50))

{

DisplayProgress(tasks);

}

Console.SetCursorPosition(0, urls.Length);

}

private static Task<WebResponse>

DisplayPageSizeAsync(string url, int line)

{

WebRequest webRequest = WebRequest.Create(url);

WebRequestState state =

new WebRequestState(webRequest, line);

Write(state, url + " ");

return Task<WebResponse>.Factory.FromAsync(

webRequest.BeginGetResponse,

GetResponseAsyncCompleted, state);

}

private static WebResponse GetResponseAsyncCompleted(

IAsyncResult asyncResult)

{

WebRequestState completedState =

(WebRequestState)asyncResult.AsyncState;

HttpWebResponse response =

(HttpWebResponse)completedState.WebRequest

.EndGetResponse(asyncResult);

Stream stream =

response.GetResponseStream();

using (StreamReader reader =

new StreamReader(stream))

{

int length = reader.ReadToEnd().Length;

Write(

completedState, FormatBytes(length));

}

return response;

}

private static void Write(

WebRequestState completedState, string text)

{

lock (ConsoleSyncObject)

{

Console.SetCursorPosition(

completedState.ConsoleColumn,

completedState.ConsoleLine);

Console.Write(text);

completedState.ConsoleColumn +=

text.Length;

}

}

private static void DisplayProgress(

Task[] tasks)

{

for (int i = 0; i < tasks.Length; i++)

{

if (!tasks[i].IsCompleted)

{

DisplayProgress(

(WebRequestState)tasks[i]

.AsyncState);

}

}

}

private static void DisplayProgress(

WebRequestState state)

{

lock (ConsoleSyncObject)

{

int left = state.ConsoleColumn;

int top = state.ConsoleLine;

if (left >= Console.BufferWidth -

int.MaxValue.ToString().Length)

{

left = state.Url.Length;

Console.SetCursorPosition(left, top);

Console.Write("".PadRight(

Console.BufferWidth –

state.Url.Length));

state.ConsoleColumn = left;

}

Write(state, ".");

}

}

static public string FormatBytes(long bytes)

{

string[] magnitudes =

new string[] { "GB", "MB", "KB", "Bytes" };

long max =

(long)Math.Pow(1024, magnitudes.Length);

return string.Format("{1:##.##} {0}",

magnitudes.FirstOrDefault(

magnitude =>

bytes > (max /= 1024) )?? "0 Bytes",

(decimal)bytes / (decimal)max).Trim();

}

}

class WebRequestState

{

public WebRequestState(

WebRequest webRequest, int line)

{

WebRequest = webRequest;

ConsoleLine = line;

ConsoleColumn = 0;

}

public WebRequestState(WebRequest webRequest)

{

WebRequest = webRequest;

}

public WebRequest WebRequest { get; private set; }

public string Url

{

get

{

return WebRequest.RequestUri.ToString();

}

}

public int ConsoleLine { get; set; }

public int ConsoleColumn { get; set; }

}Output 2

https://www.habitat-spokane.org ..9.18 KB

https://www.partnersintl.org .........14.74 KB

https://www.iassist.org .17.12 KB

https://www.fh.org ...................35.09 KB

https://www.worldvision.org ............54.56 KBConnecting a Task with the APM method pair is relatively easy. The overload used in Listing 4 takes three parameters. First, there is the BeginX method delegate (webRequest.BeginGetResponse). Next is a delegate that matches the EndX method. Although the EndX method (webRequest.EndGetResponse) could be used directly, passing a delegate (GetResponseAsyncCompleted) and using the CPS allows additional completion activity to execute. The last parameter is the state parameter, similar to what the BeginX method accepts.

One of the advantages of invoking a pair of APM methods using the TPL is that we don’t have to worry about signaling the conclusion of the AsyncCallback method. Instead, we monitor the Task for completion. As a result, WebRequestState no longer needs to contain a ManualResetEventSlim.

Using the TPL and ContinueWith() to Call an APM Method

Another option when calling TaskFactory.FromAsync() is to pass the EndX method directly and then to use ContinueWith() for any follow-up code. The result is that you have a single object to represent any kind of asynchronous operation and, therefore, you can start composing task-based operations together, even if the underlying implementation is APM-based. In addition, you can query the continue-with-Task parameter (see continueWithTask in Listing 5) for the result (continueWithTask.Result) rather than storing a means to access the EndX method via an async-state object or using closure and an anonymous delegate (we store WebRequest in Listing 4).

Listing 5: Using the TPL to Call an APM Method Using ContinueWith()

// ...

private static Task

DisplayPageSizeAsync(string url, int line)

{

WebRequest webRequest = WebRequest.Create(url);

WebRequestState state =

new WebRequestState(webRequest, line);

Write(state, url + " ");

return Task<WebResponse>.Factory.FromAsync(

webRequest.BeginGetResponse,

webRequest.EndGetResponse, state)

.ContinueWith(

(antecedent, antecedentState) =>

{

Stream stream =

antecedent.Result.

GetResponseStream();

using (StreamReader reader =

new StreamReader(stream))

{

int length =

reader.ReadToEnd().Length;

Write(state,

FormatBytes(length).ToString());

}

}, state);

}

// ...Notice that for the state to be passed into the Task returned from ContinueWith(), the ContinueWith() call explicitly includes antecedentState in the delegate in addition to having it as a parameter.

Using TAP to Call an APM Method

Given that TAP is essentially designed for handling the continuation tasks, an obvious enhancement (albeit one depending on C# 5.0) is to use async/await rather than ContinueWith(), as shown in Listing 6.

Listing 6: Using TAP to Call the APM

// ...

private async static Task

DisplayPageSizeAsync(string url, int line)

{

WebRequestState state =

new WebRequestState(url, line);

Write(state, url + " ");

WebRequest webRequest = WebRequest.Create(url);

WebResponse webResponse =

await Task<WebResponse>.Factory.FromAsync(

webRequest.BeginGetResponse,

webRequest.EndGetResponse, state);

Stream stream =

webResponse.GetResponseStream();

using (StreamReader reader =

new StreamReader(stream))

{

int length = reader.ReadToEnd().Length;

Write(state,

FormatBytes(length).ToString());

}

}

// ...Beginner Topic

Synchronizing Console Using Lock

In Listing 4, we repeatedly change the location of the console’s cursor and then proceed to write text to the console. Since multiple threads are executing that are also writing to the console, possibly changing the cursor location as well, we need to synchronize changes to the cursor location with write operations so that together they are atomic.

Listing 4 includes a ConsoleSyncObject of type object as the synchronization lock identifier. Using it within a lock construct whenever we are moving the cursor or writing to the console prevents an interim update between the move and write operations to the console. Notice that even one-line Console.WriteLine() statements are surrounded with lock. Although they will be atomic, we don’t want them to interrupt a different block that is not atomic. To ensure this outcome, all console changes require the synchronization as long as there are multiple threads of execution.

Asynchronous Delegate Invocation

One specific implementation of the APM pattern is “asynchronous delegate invocation,” which leverages special C# compiler-generated code on all delegate data types. Given a delegate instance of Func<string, int>, for example, there is an APM pair of methods available on the instance:

System.IAsyncResult BeginInvoke(

string arg, AsyncCallback callback, object @object)

int EndInvoke(IAsyncResult resultThe result is that you can call any delegate (and therefore any method) synchronously just by using the C# compiler-generated methods.

Unfortunately, the underlying technology used by the asynchronous delegate invocation pattern is an end-of-further-development technology for distributed programming known as remoting. Although Microsoft still supports the use of asynchronous delegate invocation and for the foreseeable future it will continue to function as it does today, the performance characteristics are suboptimal given other approaches—namely, Thread, ThreadPool, and the TPL. Given this reality, developers should favor one of these alternatives rather than implementing new development using the asynchronous delegate invocation API. Further discussion of this pattern is included in the Advanced Topic text that follows so that developers who encounter it will understand how it works.

Advanced Topic

Asynchronous Delegate Invocation in Detail

With asynchronous delegate invocation, you do not code using an explicit reference to Task or Thread. Instead, you use delegate instances and the compiler-generated BeginInvoke() and EndInvoke() methods—whose implementation requests threads from the ThreadPool. Consider the code in Listing 7.

Listing 7: Asynchronous Delegate Invocation

using System;

public class Program {

public static void Main(string[] args) {

Console.WriteLine("Application started....");

Console.WriteLine("Starting thread....");

Func < int, string > workerMethod =

PiCalculator.Calculate;

IAsyncResult asyncResult =

workerMethod.BeginInvoke(500, null, null);

// Display periods as progress bar.

while (!asyncResult.AsyncWaitHandle.WaitOne(

100, false)) {

Console.Write('.');

}

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine("Thread ending....");

Console.WriteLine(

workerMethod.EndInvoke(asyncResult));

Console.WriteLine(

"Application shutting down....");

}

}The results of Listing 7 appear in Output 3.

Output 3

Application started....

Starting thread....

.........................

Thread ending....

3.14159265358979323846264338327950288419716939937510582097494459230781640628620899862803482534211706798214808651328230664709384460955058223172535940812848111745028410270193852110555964462294895493038196442881097566593344612847564823378678316527120190914564856692346034861045432664821339360726024914127372458700660631558817488152092096282925409171536436789259036001133053054882046652138414695194151160943305727036575959195309218611738193261179310511854807446237996274956735188575272489122793818301194912

Application shutting down....Main() begins by assigning a delegate of type Func<int, string> that is pointing to PiCalculator.Calculate(int digits).

Next, the code calls BeginInvoke(). This method starts the PiCalculator.Calculate() method on a thread from the thread pool and then returns immediately. This allows other code to run in parallel with the pi calculation. In this example, we print periods while waiting for the PiCalculator.Calculate() method to complete.

We poll the status of the delegate using IAsyncResult.AsyncWaitHandle.WaitOne() on asyncResult—the same mechanism available on APM. As a result, the code prints periods to the screen each second during which the PiCalculator.Calculate() method is executing.

Once the wait handle signals, the code calls EndInvoke(). As with all APM implementations, it is important to pass to EndInvoke() the same IAsyncResult reference returned when calling BeginInvoke(). In this example, EndInvoke() doesn’t block because we poll the thread’s state in the while loop and call EndInvoke() only after the thread has completed.

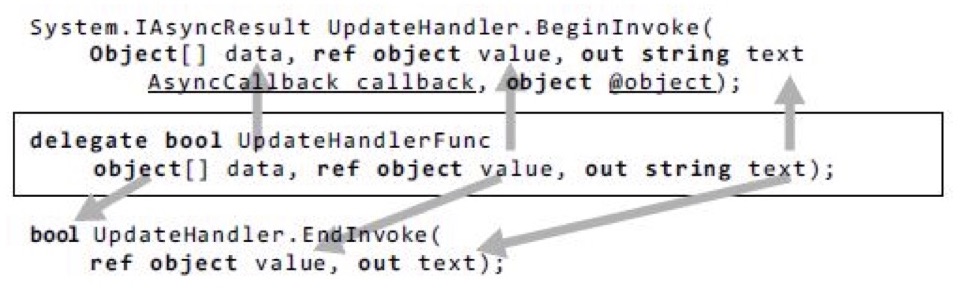

The example in Listing 5 passed an integer and received a string—the signature of Func<int, string>. The key feature of asynchronous delegate invocation, however, is that passing data in and out of the target invocation is trivial; it just lines up with the synchronous method signature as it did in the APM pattern. Consider a delegate type that includes out and ref parameters, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Delegate Parameter Distribution to BeginInvoke() and EndInvoke()

(Although commonly encountered, this example intentionally doesn’t use Func or Action because generics don’t allow ref and out modifiers on type parameters.)

The BeginInvoke() method matches the delegate signature except for the additional AsyncCallback and object parameters. Like the IAsyncResult return, the additional parameters correspond to the standard APM parameters specifying a callback and passing state object. Similarly, the EndInvoke() method matches the original signature except that only outgoing parameters appear. Since object[] data is only incoming, it doesn’t appear in the EndInvoke() method. Also, since the EndInvoke() method concludes the asynchronous call, its return matches the original delegate’s return.

Because all delegates include the C# compiler-generated BeginInvoke() and EndInvoke() methods used by the asynchronous delegate invocation pattern, invoking any method synchronously—especially given Func and Action delegates—becomes relatively easy. Furthermore, it is a simple matter for the caller to invoke a method asynchronously regardless of whether the API programmer explicitly implemented it.

Before the TPL became available, the asynchronous delegate invocation pattern was significantly easier to use than the alternatives—a factor that encouraged programmers to use it when an API didn’t provide explicit asynchronous calling patterns. However, apart from support for .NET 3.5 and earlier frameworks, the advent of the TPL diminished the need to use the asynchronous delegate invocation approach, if it is necessary at all.

The Event-Based Asynchronous Pattern

Thus far we’ve assumed that an asynchronous method will return a task; the caller is notified that the asynchronous work is completed when the status and result of the task become set. Doing so may, in turn, cause completions of the task to execute asynchronously as well. Although this pattern is common and powerful, it is not the only option for dealing with asynchrony. Notably, the Event-based Asynchronous Pattern (EAP) is often used for long-running asynchronous work (See Concurrent Programming on Windows by Joe Duffy (Addison-Wesley, 2009), pp. 421–426, for more information).

A method that uses the EAP typically has a name that ends in Async, returns void, and has no out parameters. EAP methods also typically take an object or generic parameter that contains caller-determined state that is associated with the asynchronous work, and sometimes they take a cancellation token if the asynchronous work is cancellable. For example, if we had an EAP method that computes a given number of digits of pi and returns them in a string, the signature of the method might be

void CalculateAsync(int digits)or

void CalculateAsync(int digits, object state, CancellationToken ct)What is clearly missing from these signatures is the result. The asynchronous methods we’ve seen so far would return a Task<string> that could be used to fetch the asynchronously computed value after the computation has finished. In contrast, the EAP methods have no return value.

We have not yet seen the “event” part of the Event-based Asynchronous Pattern. The method is associated with an event; the caller of the EAP method registers an event handler on the associated event and then calls the method. The method starts the asynchronous work and returns; when the asynchronous work completes, the event is fired, and the handler executes. The event arguments passed to the handler contain the computed string, and any other information that the asynchronous method assumes would be useful to the listener, such as the caller-provided state, information about any exceptions or cancellations that occurred during the asynchronous operation, and so on. (Unsurprisingly, the exact information that would be available on a task object is instead made available in the event handler arguments.)

In Listing 8, we show one way to use task-based asynchrony as an implementation detail of an EAP method. The EAP method CalculateAsync<TState>() has associated with it the CalculateCompleted event. The asynchronous method creates a task (which, by default, will run on a thread obtained from the thread pool) to do the calculation. The continuation of that task triggers the event when the task completes.

Listing 8: Event-Based Asynchronous Pattern

using System;

using System.ComponentModel;

using System.Threading;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using AddisonWesley.Michaelis.EssentialCSharp.Shared;

partial class PiCalculation {

public void CalculateAsync < TState > (

int digits,

CancellationToken cancelToken =

default (CancellationToken),

TState userState =

default (TState)) {

SynchronizationContext.

SetSynchronizationContext(

AsyncOperationManager.SynchronizationContext);

// Ensure the continuation runs on the current thread, so that

// the event will be raised on the same thread that

// called this method in the first place.

TaskScheduler scheduler =

TaskScheduler.

FromCurrentSynchronizationContext();

Task.Run(

() => {

return PiCalculator.Calculate(digits);

}, cancelToken)

.ContinueWith(

continueTask => {

Exception exception =

continueTask.Exception == null ?

continueTask.Exception :

continueTask.Exception.

InnerException;

CalculateCompleted(

typeof (PiCalculator),

new CalculateCompletedEventArgs(

continueTask.Result,

exception,

cancelToken.IsCancellationRequested,

userState));

}, scheduler);

}

public event

EventHandler < CalculateCompletedEventArgs >

CalculateCompleted = delegate {};

public class CalculateCompletedEventArgs

: AsyncCompletedEventArgs {

public CalculateCompletedEventArgs(

string value,

Exception error,

bool cancelled,

object userState): base(

error, cancelled, userState) {

Result = value;

}

public string Result {

get;

private set;

}

}

}In Listing 8, as with the async/await approach, we wish to ensure that the continuation that fires the event is always run on the same thread on which the original asynchronous method was run. To achieve this goal, we request the synchronization context from the TaskScheduler class. As this is a console application, the current thread has no synchronization (causing it to depend on the thread pool by default), so Listing 8 shows creation of the default context first.

As mentioned earlier, EAP methods are often used for long-running asynchronous operations. Long-running operations frequently provide not only notification when the task completes, fails, or is canceled, but also occasional progress updates. This sort of information is particularly useful when the user interface displays the progress of the long-running asynchronous operation with some sort of progress bar or other indicator. The standard way to do so in an EAP method is to associate the method with a second event named ProgressChanged of type ProgressChangedEventHandler.

The EAP method and its associated event (or events, if the method produces progress updates) are typically instance members, not static members. This makes it easier to support multiple concurrent operations because each separate operation can be associated with a different instance.

Background Worker Pattern

Another pattern that provides operation status and the possibility of cancellation is the background worker pattern, a specific implementation of EAP. The .NET Framework 2.0 (or later) includes a BackgroundWorker class for programming this type of pattern.

Listing 9 is an example of this pattern—again calculating pi to the number of digits specified.

Listing 9: Using the Background Worker API

using System;

using System.Threading;

using System.ComponentModel;

using System.Text;

public class PiCalculator {

public static BackgroundWorker calculationWorker =

new BackgroundWorker();

public static AutoResetEvent resetEvent =

new AutoResetEvent(false);

public static void Main() {

int digitCount;

Console.Write(

"Enter the number of digits to calculate:");

if (int.TryParse(

Console.ReadLine(), out digitCount)) {

Console.WriteLine("ENTER to cancel");

// C# 2.0 syntax for registering delegates.

calculationWorker.DoWork += CalculatePi;

// Register the ProgressChanged callback.

calculationWorker.ProgressChanged +=

UpdateDisplayWithMoreDigits;

calculationWorker.WorkerReportsProgress =

true;

// Register a callback for when the calculation completes.

calculationWorker.RunWorkerCompleted +=

new RunWorkerCompletedEventHandler(

Complete);

calculationWorker.

WorkerSupportsCancellation = true;

// Begin calculating pi for up to digitCount digits.

calculationWorker.RunWorkerAsync(

digitCount);

Console.ReadLine();

// If cancel is called after the calculation

// has completed, it doesn't matter.

calculationWorker.CancelAsync();

// Wait for Complete() to run.

resetEvent.WaitOne();

} else {

Console.WriteLine(

"The value entered is an invalid integer.");

}

}

private static void CalculatePi(

object sender, DoWorkEventArgs eventArgs) {

int digits = (int) eventArgs.Argument;

StringBuilder pi =

new StringBuilder("3.", digits + 2);

calculationWorker.ReportProgress(

0, pi.ToString());

// Calculate rest of pi, if required.

if (digits > 0) {

for (int i = 0; i < digits; i += 9) {

// Calculate next i decimal places.

int nextDigit =

PiDigitCalculator.StartingAt(

i + 1);

int digitCount =

Math.Min(digits - i, 9);

string ds =

string.Format("{0:D9}", nextDigit);

pi.Append(ds.Substring(0, digitCount));

// Show current progress.

calculationWorker.ReportProgress(

0, ds.Substring(0, digitCount));

// Check for cancellation.

if (

calculationWorker.CancellationPending) {

// Need to set Cancel if you want to

// distinguish how a worker thread completed--

// i.e., by checking

//RunWorkerCompletedEventArgs.Cancelled.

eventArgs.Cancel = true;

break;

}

}

}

eventArgs.Result = pi.ToString();

}

private static void UpdateDisplayWithMoreDigits(

object sender,

ProgressChangedEventArgs eventArgs) {

string digits = (string) eventArgs.UserState;

Console.Write(digits);

}

static void Complete(

object sender,

RunWorkerCompletedEventArgs eventArgs) {

// ...

}

}

public class PiDigitCalculator {

// ...

}Establishing the Pattern

The process of hooking up the background worker pattern is as follows:

- Register the long-running method with the

BackgroundWorker.DoWorkevent. In this example, the long-running task is the call toCalculatePi(). - To receive progress or status notifications, hook up a listener to

BackgroundWorker.ProgressChangedand setBackgroundWorker.WorkerReportsProgressto true. In Listing 9, theUpdateDisplayWithMoreDigits()method takes care of updating the display as more digits become available. - Register a method (

Complete()) with theBackgroundWorker.RunWorkerCompletedevent. - Assign the

WorkerSupportsCancellationproperty to support cancellation. Once this property is assigned the value true, a call toBackgroundWorker.CancelAsyncwill set theDoWorkEventArgs.CancellationPendingflag. - Within the

DoWork-providedmethod (CalculatePi()), check theDoWorkEventArgs.CancellationPendingproperty and exit the method when it is true. - Once everything is set up, start the work by calling

RunWorkerAsync()and providing a state parameter that is passed to the specifiedDoWork()method.

When you break it into steps, the background worker pattern is relatively easy to follow and, true to EAP; it provides explicit support for progress notification. The drawback is that you cannot use it arbitrarily on any method. Instead, the DoWork() method must conform to a System.ComponentModel.DoWorkEventHandler delegate, which takes arguments of type object and DoWorkEventArgs. If this isn’t the case, a wrapper function is required—something fairly trivial using anonymous methods. The cancellation- and progress-related methods also require specific signatures, but these are in control of the programmer setting up the background worker pattern.

Exception Handling

If an unhandled exception occurs while the background worker thread is executing, the RunWorkerCompletedEventArgs parameter of the RunWorkerCompleted delegate (Completed’s eventArgs) will have an Error property set with the exception. As a result, checking the Error property within the RunWorkerCompleted callback in Listing 10 provides a means of handling the exception.

Listing 10: Handling Unhandled Exceptions from the Worker Thread

// ...

static void Complete(

object sender, RunWorkerCompletedEventArgs eventArgs) {

Console.WriteLine();

if (eventArgs.Cancelled) {

Console.WriteLine("Cancelled");

} else if (eventArgs.Error != null) {

// IMPORTANT: check error to retrieve any exceptions.

Console.WriteLine(

"ERROR: {0}", eventArgs.Error.Message);

} else {

Console.WriteLine("Finished");

}

resetEvent.Set();

}

// ...It is important that the code check eventArgs.Error inside the RunWorkerCompleted callback. Otherwise, the exception will go undetected—it won’t even be reported to AppDomain.

Dispatching to the Windows UI

One other important threading concept relates to user interface development using the System.Windows.Forms and System.Windows namespaces. The Microsoft Windows suite of operating systems uses a single-threaded, message-processing–based user interface. As a consequence, only one thread at a time should access the user interface, and code should marshal any alternative thread interaction via the Windows message pump. Fortunately, thanks to the fact that TAP uses the synchronization context when executing the continuation task, calls following an await expression call can freely invoke the UI API without concern for dispatching invocations to the UI thread. Unfortunately, in prior versions of C#, this was not the case. Instead, invoking a UI method on the UI thread required special invocation logic both for Windows Forms and for the Windows Presentation Framework API, as we discuss in the following sections.

Windows Forms

When programming against Windows Forms, the process of checking whether UI invocation is allowable from a thread involves calling a component’s InvokeRequired property to determine whether marshalling is necessary. If InvokeRequired returns true, marshalling is necessary and can be implemented via a call to Invoke(). Internally, Invoke() will check InvokeRequired anyway, but it can be more efficient to do so beforehand explicitly. Listing 11 demonstrates this pattern.

Listing 11: Accessing the User Interface via Invoke()

using System;

using System.Drawing;

using System.Threading;

using System.Windows.Forms;

class Program: Form {

private System.Windows.Forms.ProgressBar _ProgressBar;

[STAThread]

static void Main() {

Application.Run(new Program());

}

public Program() {

InitializeComponent();

// Use Task.Factory.StartNew for .NET 4.0.

Task task = Task.Run((Action) Increment);

}

void UpdateProgressBar() {

if (_ProgressBar.InvokeRequired) {

MethodInvoker updateProgressBar =

UpdateProgressBar;

_ProgressBar.BeginInvoke(updateProgressBar);

} else {

_ProgressBar.Increment(1);

}

}

private void Increment() {

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

UpdateProgressBar();

Thread.Sleep(100);

}

if (InvokeRequired) {

// Close cannot be called directly from a non-UI thread.

Invoke(new MethodInvoker(Close));

} else {

Close();

}

}

private void InitializeComponent() {

_ProgressBar = new ProgressBar();

SuspendLayout();

_ProgressBar.Location = new Point(13, 17);

_ProgressBar.Size = new Size(267, 19);

ClientSize = new Size(292, 53);

Controls.Add(this._ProgressBar);

Text = "Multithreading in Windows Forms";

ResumeLayout(false);

}

}This program displays a window containing a progress bar that automatically starts incrementing. Once the progress bar reaches 100 percent, the dialog box closes.

In Listing 11, notice that you have to check InvokeRequired twice, and then the marshal calls across to the user interface thread if it returns true. In both cases, the marshalling involves instantiating a MethodInvoker delegate that is then passed to Invoke(). Since marshalling across to another thread could be relatively slow, an asynchronous invocation of the call is also available via BeginInvoke() and EndInvoke().

Invoke(), BeginInvoke(), EndInvoke(), and InvokeRequired constitute the members of the System.ComponentModel.ISynchronizeInvoke interface that is implemented by System.Windows.Forms.Control, from which Windows Forms controls derive.

Windows Presentation Foundation

Achieving the same marshalling check on the Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) platform involves a slightly different approach. WPF includes a static member property called Current of type DispatcherObject on the System.Windows.Application class. Calling CheckAccess() on the dispatcher serves the same function as InvokeRequired on controls in Windows Forms.

Listing 12 demonstrates this approach with a static UIAction object. Whenever a developer wants to call a method that might interact with the user interface, she simply calls UIAction.Invoke() and passes a delegate for the UI code she wishes to call. This, in turn, checks the dispatcher to see if marshalling is necessary and responds accordingly.

Listing 12: Safely Invoking User Interface Objects

using System;

using System.Windows;

using System.Windows.Threading;

public static class UIAction {

public static void Invoke < T > (

Action < T > action, T parameter) {

Invoke(() => action(parameter));

}

public static void Invoke(Action action) {

DispatcherObject dispatcher =

Application.Current;

if (dispatcher == null ||

dispatcher.CheckAccess() ||

dispatcher.Dispatcher == null

) {

action();

} else {

SafeInvoke(action);

}

}

// We want to catch all exceptions here so we can rethrow them.

private static void SafeInvoke(Action action) {

Exception exceptionThrown = null;

Action target = () => {

try {

action();

} catch (Exception exception) {

exceptionThrown = exception;

}

};

Application.Current.Dispatcher.Invoke(target);

if (exceptionThrown != null) {

// Use ExceptionDispatchInfo.Throw() for .NET 4.5+.

throw exceptionThrown;

}

}

}One additional feature in the UIAction of Listing 12 is the marshalling of any exceptions on the UI thread that may have occurred. SafeInvoke() wraps all requested delegate calls in a try/catch block; if an exception is thrown, it saves the exception and then re-throws it once the context returns to the calling thread. In this way, UIAction avoids throwing unhandled exceptions on the UI thread.

Want More?

Have any questions or comments on Multithreading? Post them below.

Comments are closed.